Palms: Planting, Growing and Caring

Contents

Palm trees in a nutshell

- Palm trees boast a majestic silhouette that instantly brings an exotic touch!

- They feature a very straight, imposing trunk, topped with lush foliage

- They bear very large leaves, which can be pinnate or palmate

- Palm trees are highly ornamental plants

- They generally prefer sunny positions and well-drained soils

- They’re the perfect plants to add an exotic flair to your garden!

- Some species are very hardy and can easily be grown outdoors in northern France.

Our Expert's Word

Palm trees are truly unique plants: they form a large plant group, the Arecaceae family, and are immediately recognisable – they don’t resemble other plants. They impress us with their majestic silhouette, composed of a very straight trunk, topped by a crown of leaves. These leaves are always very large, taking the form of palm fronds (palmate leaves) or feather-like fronds (pinnate leaves). Often green, they can also display beautiful bluish or grey hues.

There are many varieties of palm trees: the magnificent Phoenix (including date palms and Canary Island date palms), windmill palms (sometimes called Chinese windmill palms), as well as Washingtonia, and dwarf palms Chamaerops humilis… There are also indoor palms, like Areca palms, but here we’ll mainly focus on outdoor palm trees for the garden.

They’ll obviously be easier to grow if you live in the Mediterranean region, however some palm trees are very cold-hardy and suitable for outdoor cultivation even in northern France! They should be planted in spring, in a sunny spot sheltered from wind, in well-draining soil. Small palms can be grown in pots or containers and placed on a terrace! In the ground they require little maintenance, but need more attention when grown in containers. In this case, you’ll need to water them occasionally, provide some fertiliser and repot them on average every three years.

Palm trees are impressive and fascinating plants. They have the power to lift us from surrounding gloom and transport us to sunny climes. They make us dream by instantly adding a dose of exoticism to the garden. The very name of palm trees evokes postcard-perfect scenery, a paradise beach with coconut palms and turquoise waters… So why not add some exotic flair to your garden?

Description and botany

Botanical data

- Latin name Trachycarpus sp., Chamaerops sp., Washingtonia sp. ...

- Family Arecaceae

- Common name Palm tree

- Flowering often in spring or summer

- Height highly variable, often up to 15-20 metres

- Exposure full sun

- Soil type well-draining, rather sandy

- Hardiness very variable. Down to -20°C for the hardiest

The palm trees are plants with a straight and imposing trunk, called a stipe, topped by a crown of large leaves, either pinnate or palmate. They are truly unique plants, quite ancient, and form a highly diverse group. They belong to the botanical family Arecaceae, comprising between 2500 and 2700 species, spread across 185 different genera.

Palm trees have a wide global distribution: many species originate from Indonesia and Southeast Asia, others come from Africa or America. Only two palm trees grow naturally in Europe, in the Mediterranean region: Chamaerops humilis and Phoenix theophrasti. Many species are also found on islands in the Indian Ocean. Their presence on islands and in regions with very mild climates has made them a true symbol of holidays, relaxation, and exoticism.

In the wild, palm trees are found in very diverse environments. Some come from tropical forests, others grow in deserts, and others still in mangroves (like Nypa fruticans)… They can grow by the sea as well as at high altitudes (such as in the Andes Mountains).

Appreciated for the exotic touch they bring, they have found their place in gardens, but they are also cultivated for food or crafts: rattan, raffia, coconuts, dates, palm oil, vegetable ivory… the uses of palm trees are numerous!

Palm trees are not trees: they generally do not branch, lack wood or branches, and cannot truly grow in diameter, only in height. Botanically, it would be more accurate to consider them as giant herbs rather than trees. The trunk of palm trees is referred to as a “stipe.” This is actually made up of the base of the petioles, which accumulate as the plant grows.

In the wild, palm trees grow in varied habitats. The date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) is found in desert regions (photo Franzfoto), the coconut palm (Cocos nucifera) on beaches by the sea (photo Kalamazadkhan), while Nypa fruticans grows in mangroves (photo Luis Argerich)

Palm trees have only one apical bud, at the top of the stipe, which allows them to grow taller. Once the stipe is formed, it can hardly increase in diameter (except in a few cases where cells swell with water, slightly thickening the trunk…). If the terminal bud dies, the palm tree will perish, as it can no longer grow.

The shape of palm trees is distinctive. Most have a long stipe, very straight and imposing, topped by a cluster of leaves. It is rare for palm trees to branch: there is usually only one stipe. However, some species form clumps and have a bushy habit, like the Chamaerops humilis. The Nannhorops ritchieana is also a cespitose palm that produces multiple stipes. There are even climbing palms, like those in the genus Calamus! The stipes of climbing palms can reach up to 180 or 200 metres in length! They usually cling to other plants using their spines.

The height of palm trees varies greatly. The most commonly cultivated in gardens reach up to 15-20 metres, but there are also dwarf palm trees, like Chamaerops humilis, with a bushy habit. In nature, there are no strict rules: the tallest species reach between 50 and 60 metres in height… while the smallest are only a few dozen centimetres tall!

The stipe of palm trees can be quite slender or much more massive. It is often very straight, although coconut palms seen on beaches have arched stipes, sometimes very leaning. The Chilean wine palm (Jubaea chilensis) has a particularly imposing and very smooth stipe, which can measure four metres in circumference at the base!

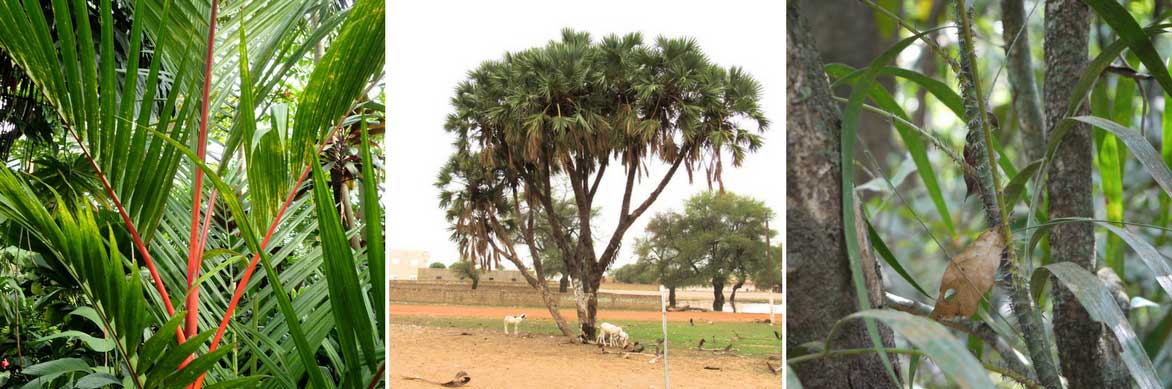

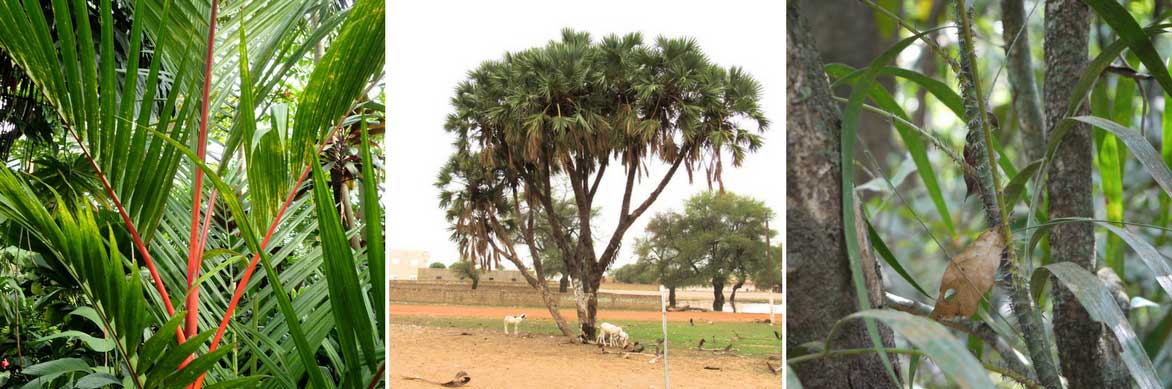

In some species, like the Trachycarpus fortunei, the stipe is covered in brown fibres. The leaves can also leave scars that remain visible on the trunk, creating patterns (horizontal marks, diamonds, etc.). Palms in the genus Hyophorbe have a swollen stipe, earning them the name Bottle Palm. There are also species with bright red trunks, in the genus Cyrtostachys. The stipe can also be very thorny, like in Trithrinax campestris!

Palm trees form a large group, some of which stand out for their originality. The bright red stipe of Cyrtostachys renda (Krzysztof Ziarnek, Kenraiz), the branched stipe of Hyphaene thebaica (photo Malcolm Manners), and the climbing palm Calamus thwaitesii (photo Dinesh Valke)

Most palm trees flower in spring or summer. Their flowers are grouped into inflorescences, more or less branched, sometimes very impressive! They are usually located at the base of the lowest leaves but can also be placed in the middle of the leaf cluster or at the top.

The flowers are small and often white, cream, or yellow. They consist of three sepals, three petals, usually six stamens, sometimes many more. Most often, the flowers are unisexual. They are pollinated by insects or wind.

Some palm species bear only male or only female flowers on a single plant: they are dioecious. This is the case with Trachycarpus fortunei. Both male and female plants are needed to produce seeds. Other palms have both male and female flowers on the same plant: they are monoecious. This is the case with Sabal palmetto.

Palm trees have very large, thick, leathery leaves. They are divided, split into thin, elongated segments, sometimes pointed at the tip. The leaflets are often pleated. The leaves can also bear threads, linear fibres, like in Washingtonia filifera. Those of the Licuala grandis palm are barely divided, forming true fans!

In terms of overall shape, palm trees can have two main types of leaves: they are often palmate (fan-shaped), but can also be pinnate (like a feather, with a central axis and segments on either side). When pinnate, they are often beautifully arched, creating an elegant curve. Those of Trachycarpus and Chamaerops are palmate, while those of Phoenix or Butia are pinnate. Sometimes, the leaves take an intermediate form, called costapalmate: fan-shaped but with a central axis. They can also be much more original, like those of Caryota mitis, the Fishtail Palm! The leaves are usually green but can also take on bluish or greyish hues. They are sometimes yellow-green.

The palmate leaves of Washingtonia robusta, the original “fishtail” foliage of Caryota mitis (photo Mokkie), and the pinnate leaves of a Phoenix (photo Wiethase Hendrik)

The leaves are attached to the stipe by a thick petiole, which can be very thorny. Sometimes, the base remains on the trunk after the leaf falls. When palm leaves fall, they sometimes leave scars or patterns on the trunk. It is also quite common for old leaves, once dry, to remain attached to the stipe. This is the case with the Petticoat Palm, Washingtonia filifera. They form thick layers of dead leaves. For aesthetic reasons, they are often removed, cut away, to give a “clean” look. However, these leaves insulate and protect the trunk. It is better to leave them in place.

Palm trees have many small, fasciculated roots, very elongated. They are sparsely branched and do not increase in diameter, but they penetrate deeply into the soil. There is a palm tree with large aerial roots (stilt roots), the Socratea exorrhiza.

The fruits and seeds of palm trees are extremely varied. The fruits are berries or drupes. They can be enormous, like the nuts of the Coco de Mer (Lodoicea maldivica), or tiny. Some species produce edible fruits: such as dates (the fruits of Phoenix dactylifera), or coconuts. The fruit of the Phytelephas palm yields vegetable ivory, which can be carved into jewellery, buttons, or objects. Palm oil comes from the nut of the Elaeis guineensis palm, now intensively cultivated. Coconuts are adapted to float and be dispersed by the sea. This is how the coconut palm colonises new islands.

The seeds of Butia capitata (photo Roger Culos – Museum de Toulouse), a coconut (photo Nicolai Schäfer), and dates: fruits of the Phoenix dactylifera palm (photo Bernadette Simpson)

Some species cannot tolerate freezing temperatures, while others are quite hardy (Chamaerops humilis, Trachycarpus fortunei…). The Rhapidophyllum hystrix palm can even withstand between -20 and -25°C! Discover our collection of cold-hardy palm trees!

Conversely, there are palm trees that can be grown indoors year-round, like the Kentia, Howea forsteriana, a fairly common houseplant, as well as Chamaedorea elegans, or some Dypsis…

Read also

How to Dry Dates?The main varieties of palm trees

Phoenix canariensis - Canary Island Date Palm

- Flowering time August, September

- Height at maturity 15 m

Chamaerops humilis - Dwarf Palm

- Flowering time July, August

- Height at maturity 3,50 m

Trachycarpus fortunei - Chinese Windmill Palm

- Flowering time August to October

- Height at maturity 8 m

Butia capitata - Wine Palm

- Flowering time July, August

- Height at maturity 5 m

Jubaea chilensis - Chilean Wine Palm

- Flowering time July, August

- Height at maturity 13 m

Washingtonia filifera - California Fan Palm

- Flowering time August, September

- Height at maturity 17 m

Chamaerops humilis var. cerifera - Dwarf Fan Palm

- Flowering time July, August

- Height at maturity 3 m

Rhapidophyllum hystrix - Needle Palm

- Flowering time July, August

- Height at maturity 3 m

Trachycarpus wagnerianus - Dwarf Chusan Palm

- Flowering time July, August

- Height at maturity 6,50 m

Washingtonia robusta - Mexican Fan Palm

- Flowering time August, September

- Height at maturity 24 m

Nannorrhops ritchiana Silver

- Flowering time August, September

- Height at maturity 10 m

Discover other Phoenix

Planting a palm tree

Where to plant?

Palms represent a large and diverse group of plants. They don’t all have the same requirements. Some prefer rather arid environments, others cooler or humid conditions. Most species thrive in full sun, but a few will prefer shade or partial shade. It’s important to research the growing conditions of the species you wish to plant. Additionally, once established, palms dislike being moved.

Most palms thrive in full sun, as they require significant light exposure. However, avoid scorching locations. There are also species that can be planted in shade, such as Trachycarpus fortunei. Similarly, in southern France, the Rhapidophyllum hystrix palm will appreciate being planted in shade or partial shade.

Palms need a very well-draining substrate. They dislike waterlogged conditions and heavy, clay soils, which make them more susceptible to cold. They prefer rather sandy soils. Don’t hesitate to improve drainage when planting by adding gravel or pumice, or plant on a mound to encourage water runoff.

Most palms prefer well-draining soils, but again, this depends on the species you’re growing (there are always exceptions!). For example, Nypa fruticans, which grows wild in mangroves, will appreciate having its roots in water!

Palms generally prefer soils rich in minerals, although the Chamaerops can grow in poor soil. They also like deep soils.

Choose a location sheltered from wind if possible, as wind can damage leaves and make palms more vulnerable to cold and drought. Some species tolerate sea spray very well and can therefore be planted in coastal gardens. This is the case for Phoenix canariensis or Chamaerops humilis, for example.

You can grow smaller palms in containers (like Chamaerops humilis…) and place them on a terrace, for instance. This is a good solution if you live in a region with harsh winters or if your palm isn’t very hardy, as you can bring it into a frost-free shelter for winter. Add a drainage layer at the bottom of the pot and choose a substrate that is both well-draining and fairly rich (compost, garden soil and sand).

Palms sometimes make excellent houseplants, like Howea forsteriana or Chamaedorea, which can easily be grown indoors year-round. With their very upright, imposing and majestic silhouette, palms also make excellent avenue trees. They beautifully highlight the lines of a driveway.

Choose a suitable location with enough space for the palm to develop properly. If you only have a small garden, avoid growing the largest palms, like Jubaea chilensis.

When to plant?

We recommend planting your palm in spring, between April and June. You can plant a little earlier if you live in the Mediterranean region. Planting is still possible in summer, but avoid autumn or winter, as palms need warmth to establish well.

How to plant?

- Soak the root ball briefly in a bucket of water.

- Dig a planting hole, two to three times the size of the root ball. You can add gravel or pumice to the bottom of the hole to improve drainage. Add some compost to enrich the soil or a slow-release fertiliser.

- Place the root ball, positioning the base of the trunk at ground level or very slightly above (be careful not to bury the crown).

- Backfill with soil around the palm and firm it down.

- Water thoroughly. You can create a watering basin.

Continue watering regularly during the first year.

Caring for Palm Trees

If planted in the ground and with hardy species selected, palms are very easy to grow. When grown in pots, they require a bit more attention than when planted in the ground. They are more fragile, more sensitive to cold and drought, and need more fertiliser, etc.

**Water regularly during the first year after planting. In subsequent years, water only during prolonged dry spells.** Palms will need more frequent watering if grown in containers, as the growing medium dries out much faster. Keep the soil moist but not waterlogged, and avoid letting water sit in the saucer. Reduce watering in winter. Most palms appreciate fairly humid conditions—if the air is particularly dry, **you can mist the foliage.** This is especially important for palms grown indoors, as the air in our homes is much drier than outside.

Palms are quite nutrient-hungry plants. **We recommend applying fertiliser or well-rotted compost**, especially if grown in pots. You can also fertilise your palm with crushed horn, guano, or dried blood.

Not all palms have the same cold tolerance. Some can withstand temperatures as low as -15°C, while others struggle with even slight frosts. Check the hardiness of the palm you’re growing! **Some species require winter protection against the cold**, particularly during the first two or three years. Young palms are more sensitive to cold than mature ones. You can, for example, wrap them in **horticultural fleece**. For winter, move potted palms indoors or into a greenhouse if they are not very hardy or if you live in a cold region. Place them in a bright spot and mist the foliage if the air is dry. You can move them back outside in spring, first placing them in partial shade before gradually acclimating them to full sun to avoid scorching the leaves.

If growing your palm in a container, you’ll need to repot it regularly—on average every three years—to refresh the growing medium and move it into a slightly larger pot each time. In years when you don’t repot, you can top-dress the soil to replenish nutrients on the surface.

**Pruning palms is mainly for aesthetic purposes and isn’t strictly necessary.** We generally advise against it, as they can thrive without it, and pruning can attract pests. If you do need to prune, do so between November and March (outside the pest flight season), keep pruning light, and **apply a pruning sealant.** You can perform what’s called a “pineapple cut,” trimming the petioles well away from the trunk. This way, the base of the petioles acts as cold protection, and the plant retains the nutrients stored in these tissues. If you cut into the trunk of a palm, this could prove fatal, as palms have a single terminal bud at the top of the trunk that allows them to grow. Removing this bud risks killing the palm.

For aesthetic reasons, **it is sometimes recommended to remove dead leaves that remain attached to the trunk** (visible, for example, in *Washingtonia filifera*). However, these leaves serve a purpose: they form an insulating layer that protects the palm from cold and pests. It’s best to leave them in place.

Palm Tree Diseases and Pests

Palm trees are sometimes attacked by the butterfly Paysandisia archon. Native to South America, it has spread around the Mediterranean basin and is wreaking havoc in southern France. The caterpillars burrow tunnels into the trunk. The leaves become damaged, hole-ridden, turn yellow, dry out and become deformed. Palm trees face another enemy: the red palm weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus), a beetle native to Asia. Again, the larvae tunnel into the trunk or leaves of the palm tree, which may die rapidly.

→ Read more: “Combating the red palm weevil”

You can spot these pests by a drooping crown of leaves, fronds falling off, or their drying out and perforation… As soon as you notice their presence, you must report it to your local town hall and take steps to eliminate the pest. Given the damage they cause, controlling these pests is mandatory.

→ Read more: “The palm tree butterfly, Paysandisia archon – control and treatment”

When grown indoors or in greenhouses, palm trees may be attacked by red spider mites and scale insects. Against scale insects, spray with black soap. As for red spider mites, they thrive in dry conditions—we recommend misting the foliage. Lastly, palm trees can be attacked by the palm leaf beetle, Pistosia dactyliferae, whose larvae target the plant’s heart.

They are sometimes affected by the fungus Chalara paradoxa, which causes the terminal bud to rot and may lead to the palm tree’s death. They can also be affected by other fungal diseases such as Phytophthora palmivora or Fusarium wilt.

→ Also check out our guide: Nematodes against palm tree pests: why and how to use them in the garden?

Propagation: Sowing Palm Tree Seeds

Palms are mostly propagated by seed, although some species (such as Chamaerops humilis) produce offsets that can be removed to propagate the plant.

Sowing

Seeds vary greatly from one palm to another, both in terms of their size and the germination protocol or storage duration. We recommend researching the specific germination conditions for the species you wish to propagate. Some palms take a year to germinate, while others sprout within weeks. Some require pre-soaking the seeds in warm water, others need refrigeration before sowing (stratification). Still others need their seeds to be brushed, cleaned, or have their outer skin removed. Similarly, depending on the species, humidity and temperature requirements differ. Palms represent a very broad and diverse group, making generalisations difficult.

It is best to sow the seeds in spring. And, if possible, to do so shortly after harvesting. Some seeds remain viable for several years, while others quickly lose their ability to germinate.

- Before sowing, it is advisable to soak the seeds in warm water for at least 24 hours, or even two to three days, changing the water daily. This aids germination. For some species, chilling the seeds in the refrigerator will promote germination.

- Prepare pots by filling them with a well-draining substrate, such as a mix of compost and sand. Choose fairly deep pots, as with some species, the first emerging roots penetrate deeply into the substrate.

- Remove the seeds from the water, rinse them, and sow them.

- Cover them with a layer of substrate.

- Lightly firm the soil.

- Water gently with a fine spray.

- Optionally, place a lid or plastic bag over the pot to maintain a humid atmosphere.

Place your seedlings in a bright location but out of direct sunlight, at a temperature of at least 20°C. Again, research the specific growing conditions for your chosen species: some palms prefer temperatures between 25 and 30°C, while this may be too warm for others. Keep the substrate moist until germination occurs, misting it regularly. Be patient—some varieties can take a long time to sprout.

Once the young shoots reach around 10 cm in height, you can transplant them.

Gradually acclimatise your palms to sunlight by occasionally moving them outside before eventually placing them in full sun. Palms grow slowly at first, particularly in their early years. Their growth rate increases later on.

Companion planting in the garden

For an exotic garden, we recommend planting palm trees alongside other tropical-looking plants. Create a lush area by focusing on striking and architectural foliage, such as that of the castor bean plant, Tetrapanax papyrifera, banana trees (for example, Musa basjoo) or Colocasia ‘Pink China’… Also discover the stunning, graphic and colourful foliage of the Phormium. If you have a water feature, you can plant Gunnera manicata or tree ferns nearby. Enjoy the bright foliage of the ornamental grass Hakonechloa macra. And if you’re looking for climbing plants, opt for bougainvilleas or trumpet vines! Incorporate flowers in warm tones (red, orange, yellow…): crocosmias, red hot pokers, cannas, bulbine… Also admire the majestic blooms of Hedychium gardnerianum! The ideal setting would be to plant these exotic species near a swimming pool or pond… That way, you might just feel like you’re on holiday every time you step into your garden!

Use palm trees to create a tropical atmosphere! Trachycarpus fortunei (photo Vera Buhl), Phoenix canariensis (photo Forest & Kim Starr), Crocosmia ‘Lucifer’ (photo Vicky Brock), Tetrapanax papyrifera ‘Rex’, Kniphofia ‘Fiery Fred’ and Hedychium gardnerianum (photo J.J. Harrison)

Another interesting idea would be to plant palm trees in a Mediterranean-inspired garden, creating an exotic – holiday-like – atmosphere, but this time with a drier, less lush style. Create a rocky environment, perhaps a rockery, and incorporate aromatic plants and ornamental grasses. Choose lavenders, cotton lavenders, Stachys byzantina, Stipa tenuissima, yarrows… Favour plants with silvery foliage and fragrant species. Add a few small succulents, such as Sempervivum or Sedum, which can be tucked between stones. For a truly exotic garden, take advantage of the elegant silhouettes of yuccas, aloes and agaves. You could also add a few euphorbias or cacti. To contrast with this dry, rocky setting, consider adding a small water feature or fountain nearby.

Palm trees can also be planted as standalone specimens to showcase their elegant structure. You can place them alone in the middle of a lawn, designing the entire garden around them as a centrepiece separate from other flower beds. With their majestic, upright habit, palm trees are sometimes planted in rows along paths or roads (a common sight on the French Riviera). Finally, you can also grow palm trees in pots on a terrace, alongside citrus trees, bird of paradise plants, banana trees or passionflowers… This way, you can easily move them to a frost-free shelter during winter.

Did you know?

- Multiple uses!

Palm trees can be used for their fibres, seeds or fruits. The Raphia palm produces the fibre of the same name. From the Calamus palm, we obtain rattan, which can be woven and is also used to make furniture… Palms are also used to create thatched roofs. The fruit of the Phytelephas palm yields vegetable ivory, used to craft jewellery, buttons, decorative objects… The dragon’s blood palm, Daemonorops draco, produces a type of red resin, valued for its medicinal properties and as a dye. The fruit of the Areca palm produces betel nut or areca nut: it is chewed for its stimulant properties and appetite-suppressing effects. Some palms produce wax used to make candles.

- In food…

Palms are also plants used for food: this is of course the case with dates from the Phoenix dactylifera, and coconuts (Cocos nucifera), but also palm sugar, obtained from the Borassus flabellifer species. Similarly, the core of the trunks of several palms is edible, yielding heart of palm. Palm oil is produced by Elaeis guineensis, a species native to Africa but whose intensive cultivation causes deforestation issues, particularly in Malaysia and Indonesia. The Metroxylon sagu palm produces sago, a starch consumed especially in Papua New Guinea in the form of flatbreads. Palm wine is also made by fermenting the sap of various palms…

- Records

Palm trees are plants that break all records. The Raphia regalis has the longest leaves in the plant kingdom: they can measure up to 25 metres long and 4 to 5 metres wide! The largest seeds undoubtedly belong to the coco de mer, nicknamed the double coconut (Lodoicea maldivica): they can weigh 20 to 25 kg with a diameter of 40 to 50 cm. The world’s largest inflorescence is that of the Corypha umbraculifera: it can reach 7-8 metres in height! Among palms, the tallest is the Ceroxylon quindiuense, reaching between 50 and 60 metres in height.

- And in France…?

In France, the best region to admire palm trees is the French Riviera, with gardens such as the Villa Thuret in Antibes or the Parc Phoenix in Nice. Elsewhere in France, the greenhouses of botanical gardens sometimes house very fine collections. The Botanical Garden of Villa Thuret boasts a superb collection of palms, some quite old, including spectacular specimens of Jubaea chilensis. You can consult the book The Art of Acclimatising Exotic Plants, the Garden of Villa Thuret, by Catherine Ducatillion and Landy Blanc-Chabaud, published in 2010 by Quae editions.

Useful resources

- Our range of palm trees!

- The website of the Palm Tree Enthusiasts association, featuring a forum

- Book: Understanding Palm Trees by Pierre-Olivier Albano, published in 2002 by Edisud

- Find more botanical information about palm trees on the Plants & Botany website

- Another website with extensive information on palm tree cultivation

- Discover indoor palm trees: Chamaedorea

- Check out our tutorial: How to dry a palm frond?

- For prevention and treatment: Palm tree diseases and pests

Frequently asked questions

-

Should I cut off dead leaves?

Some palm trees retain their old leaves against the trunk once they have dried, forming a true "skirt" beneath the still-green leaves. This is the case, for example, with the Washingtonia filifera. You can prune them for aesthetic reasons, giving the palm tree a tidier appearance. However, if you live in a cold region, it's best to leave them: these leaves form a protective layer that shields the trunk from cold and pests.

-

The leaves of my palm tree are turning yellow!

The main reason palm fronds turn yellow is a lack of mineral nutrients. The plant is deficient: apply fertiliser or well-rotted compost. If grown in a pot, repot it. If your soil is chalky, mineral absorption may be blocked. Similarly, yellowing leaves can stem from watering issues: they often indicate excess moisture, or sometimes, when just the tips of the fronds yellow and dry out, a lack of water. Water while allowing the growing medium to dry out between waterings. The soil may also be too compacted, causing root suffocation. Yellowing leaves can also be caused by the Paysandisia archon moth. Check the crown's condition (is it drooping?) and look for perforations in the leaves.

-

The leaves of my palm tree have dried out

If it's the lowest leaves and the rest of the crown is in good condition, this is completely normal: some palms form a "skirt" of dead leaves, keeping them around the trunk beneath the still-green foliage.

Dry leaves can also indicate a lack of watering or an atmosphere that's too dry, especially if you're growing your palm indoors. Water regularly and don't hesitate to mist the foliage.

A palm that has suffered frost damage will also see its foliage dry out.

-

The leaves of my palm tree are perforated

You are likely dealing with the Paysandisia archon moth, an invasive species originating from Argentina and Uruguay. The larvae feed on the crown of the stipe. Reporting new infestations and controlling this pest are now mandatory.

-

The leafy crown is thinning and drooping!

If the crown is sparse and there are missing fronds at the top, the culprit may be the Paysandisia archon moth or the red palm weevil. Their larvae nibble on the upper part of the trunk and bore tunnels inside. These are two invasive species, spreading across French territory, which can quickly lead to the death of palm trees. Control of these pests is mandatory and involves spraying nematodes, using pheromone traps, or injecting insecticides into the trunk.

- Subscribe!

- Contents

Comments