The artichoke, or Cynara scolymus by its Latin name, needs no introduction. Originally a Mediterranean perennial, it dislikes frost and excess moisture but boasts many advantages. Firstly, everyone knows its culinary uses, with recipes varying by country and cultivated variety.

The artichoke also has a place in the garden—beyond the vegetable patch. Its striking silhouette, with large, deeply lobed grey leaves, catches the eye almost year-round, except during severe frosts when it succumbs to the cold.

But did you know that the artichoke is also a medicinal plant? Its use dates back to ancient times. The artichoke, as we know it today—descended from the cardoon—emerged around the end of the Middle Ages and has an effect on the hepatobiliary system.

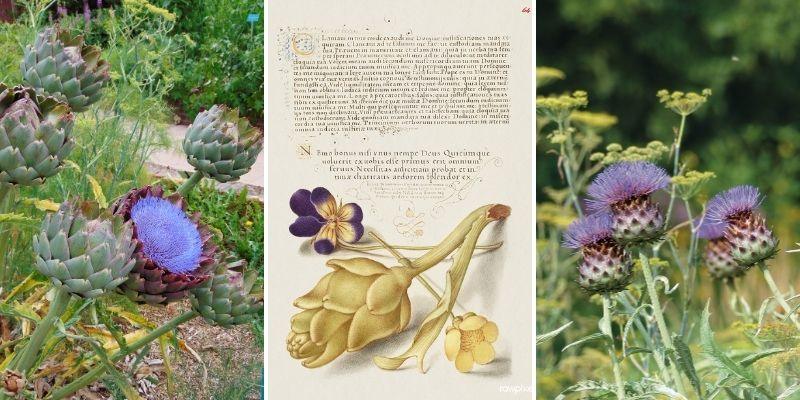

Artichoke flowers (left) and cardoon flowers (right). Centre: an old illustration of an artichoke (Photo Rawpixel Ltd).

Part used: the leaves

But let’s start at the beginning: the leaf is the part used in herbal medicine.

First, we must clarify what we mean by leaves in the artichoke. Most people think of the parts we dip delightfully into vinaigrette. Well, those aren’t the true leaves. What we actually eat are the fleshy bracts of the flower and the receptacle, commonly called the artichoke heart.

The real leaves are the large, thick, deeply lobed grey leaves growing from the base of the plant. These are the ones used to support liver health.

Don’t confuse the leaves (left) with the artichoke flowers (right).

Harvesting the leaves

Now that we’ve clarified the leaves, let’s move on to practice.

Harvest on a dry day to minimise moisture in the plant. As with all edible leaves, it’s best to pick them in spring before the flowering process begins, ensuring maximum active compounds in the harvested part. For artichokes, this means collecting the leaves before flower stems appear—if you already see small budding artichokes, the plant has likely diverted all its energy to producing them at the expense of the leaves.

You’ve now picked one or two artichoke leaves—these are very large and provide plenty of material. If you need a larger quantity, nothing stops you from repeating the process later. However, we recommend testing the drying and tasting process first to decide whether to repeat the experience.

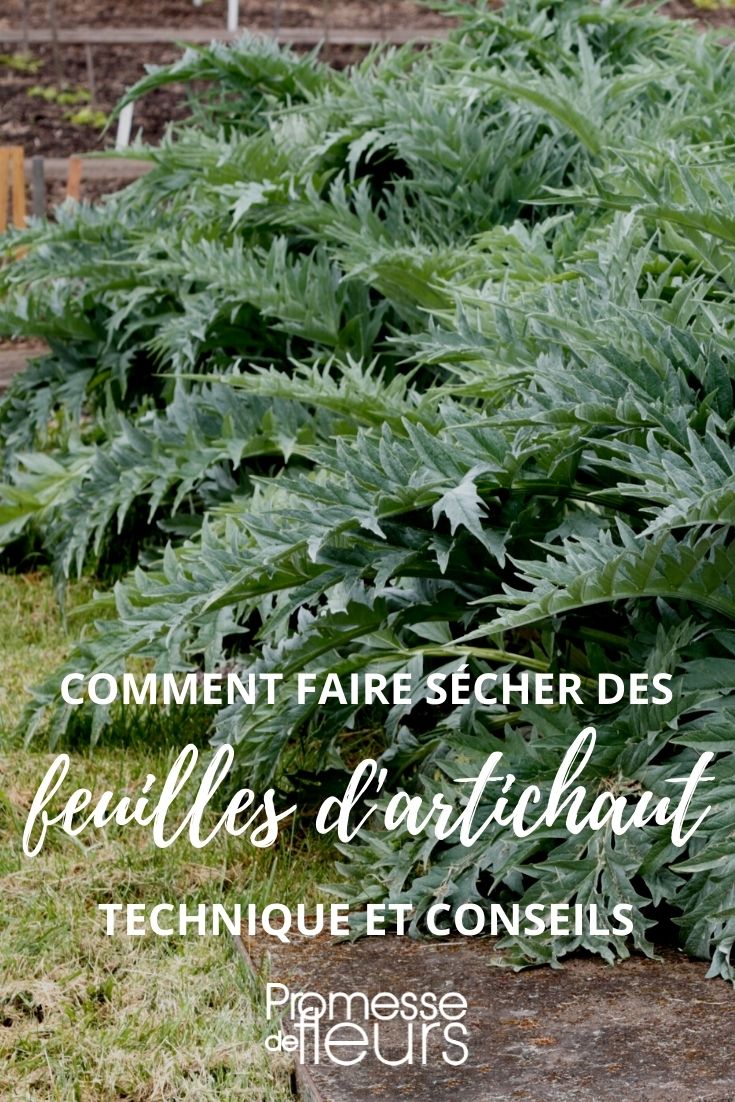

Harvest the leaves before flowers appear (Photo Filippo Giunchedi).

Drying the leaves

Now, let’s move on to drying.

Air drying

You’ll need a well-ventilated, dark space to best preserve the plant’s properties. This is especially true for artichoke leaves, which are very moist and prone to mould if not dried properly. They should dry as quickly as possible without scorching. The ideal method is spreading the leaves on racks in an attic—the perfect dark, well-ventilated spot for rapid drying.

Oven or dehydrator

If you don’t have an attic and are in a hurry, other technical solutions exist. First, the oven—if it can maintain a precise temperature of 40°C max. In this case, leave the door slightly ajar. It’s not very eco-friendly but helps remove moisture. The second option is a dehydrator, which should yield optimal results—though I haven’t personally tested this method.

Note: after drying, the leaves should be brittle but retain their grey hue. If they’ve turned brown, they’re unfit for consumption and should be discarded.

Racks used for drying medicinal plants.

The benefits of artichoke

Now that your artichoke leaves are dry, you may wonder when to use them.

Know that artichoke leaves are renowned for their liver-supporting properties. This use dates back to around the 15th century, echoing the "doctrine of signatures" attributed to Hippocrates. This theory suggests a resemblance between a plant and the human organ it treats—for example, bitterness recalling bile, as with artichoke. Scientific studies have debunked this theory’s limits, but artichoke does indeed have a choleretic effect (promoting bile production) and supports liver protection. It also has a diuretic effect.

Usage

Now that the leaves are dry and brittle, you can crumble them slightly. This makes storage easier and simplifies use. Store your preparation as you would tea, avoiding overly airtight containers where mould could develop if drying wasn’t optimal.

There you go! Your artichoke herbal tea is ready. Boil water, pour it into a large cup over a spoonful of the plant, and let it steep for about ten minutes before cooling slightly and drinking. "Drinking" may be too generous a term, as the plant is a bitter tonic. A good spoonful of honey is advised. Now we understand why so many pharmacy formulations exist to avoid this bitterness. But nothing beats the satisfaction of making your own liver-supporting tea from a plant in your garden.

Warning

For therapeutic effects, consult a herbal medicine specialist—a doctor or pharmacist. Self-medication should be avoided.

Finally, remember that no herbal tea should be consumed continuously year-round—cumulative toxicity risks cannot be ruled out. Herbal use is not trivial!

Comments