Aphid: identification and treatment

our tips to fight them naturally and effectively

Contents

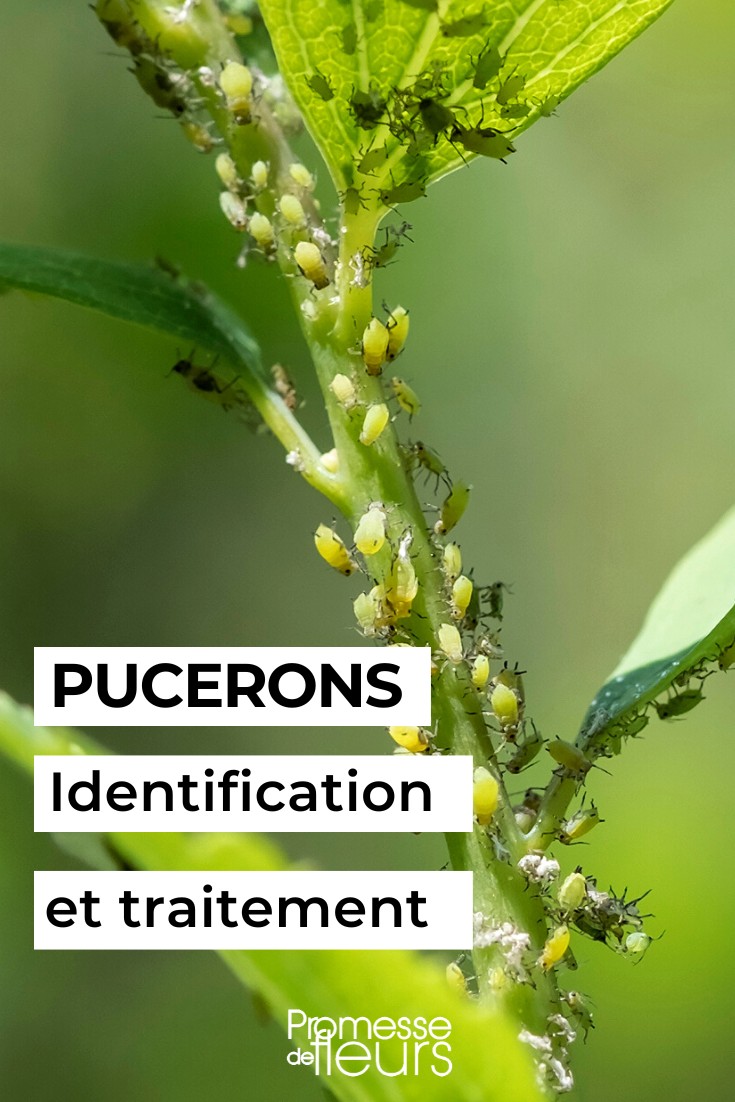

Greenfly is a small, well-known insect that populates our gardens, forming colonies on various ornamental, vegetable, or fruit plants. Gardeners often observe these colonies of black greenfly on cherry trees or green greenfly on rose bushes, among others.

An invasion of greenfly does not necessarily pose a problem: with a bit of patience, garden helpers take care of them and eventually get rid of them within a few weeks. However, greenfly can cause damage to young plants and shoots of the year, necessitating intervention. For this, there are natural, organic anti-greenfly solutions to help you effectively combat and reduce harmful infestations to your crops and plantings.

The different types of aphids

Black aphid, green aphid, aphids on roses or tomatoes… there are several hundred species of aphids on cultivated plants, but fortunately few cause real damage in gardens. Aphids are piercing and sap-sucking insects, particularly virulent in warm weather. They attack almost all species of cultivated plants, and their size ranges from 2 to 4 mm. They are often found in colonies under leaves, at the tips of shoots, or on the flower peduncles. Some species have a development cycle that occurs on several successive host plants. This means that in a single season, they move from a primary host plant to one or more secondary host plants.

Almost all species overwinter in the form of eggs laid on leaves or in the soil. These eggs will hatch into female aphids that form the first colonies. They then reproduce by parthenogenesis. Some individuals have wings to colonise other plants. Males are present in autumn to allow for sexual fertilisation before the laying of eggs.

Aphids are exploited by ants for their honeydew secretion and even go so far as to protect their herd by attacking beneficial insects that come too close.

Aphid farming by ants.

Here are some of the most frequently encountered species:

-

Black bean aphid (Aphis fabae)

Colony of black aphids at the heart of an artichoke head.

This species moves between several successive host plants. It is first found on spindle, then on viburnum, and from April onwards on vegetable crops: broad bean, beetroot, cucumber, bean, artichoke, rhubarb, as well as on poppy, dahlia, nasturtium, etc.

-

Cherry black aphid (Myzus cerasi)

Its bites cause early curling or crinkling of leaves, as well as deformation of shoots. It secretes a sweet, sticky honeydew that leads to leaf burn, drying out, and a significant reduction in yield. Sooty mould may also appear.

-

Green aphid (Myzus persicae)

The preferred primary hosts of this species are fruit trees of the genus Prunus, particularly peach. It then migrates to vegetable crops: potato, tomato, pepper, lettuce, chicory, spinach, cabbage, carrot, cucumber, melon, courgette, etc.

-

Rose green aphid (Macrosiphum rosae)

It develops on young shoots, flower buds, or on the underside of leaves. There is no need to worry in a garden that is favourable to beneficial insects, as they regulate aphid populations very well. However, keep an eye on young roses.

Colony of green aphids on a tender young rose shoot.

-

Cabbage aphid (Brevicoryne brassicae)

As its name suggests, this aphid specifically attacks cabbages and is favoured by warm, dry weather. It is light green covered with a white down and often invades cabbages from May to October. If aphids are numerous, damage can be significant on seedlings and young cabbage plants.

-

Woolly apple aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea)

This species is recognised by its whitish fluff, with winged individuals being black. It is the most dangerous aphid, particularly on young trees. In spring, rapid curling of leaves, deformation of shoots, and fruits can be observed.

-

Woolly apple root aphid (Eriosoma lanigerum)

Typical whitish secretion of the woolly apple aphid. (photo: Wikipedia)

Excessive presence results in the formation of swollen cankers on the main branches and weakening of the trees. It is recognised by the whitish wax that covers it. It overwinters in the folds of the bark at the lower part of the trees, until the roots start to grow.

-

Root woolly aphid (Pemphigus bursarius, Protrama flavescens…)

These species attack several vegetable plants at the root level, particularly lettuces that struggle to form heads and sometimes wither.

-

Yellow aphid (Cryptomyzus ribis)

It is often present in spring, under the leaves. Its bite causes characteristic swellings and the appearance of reddish colours that can be easily observed on the leaves of blackcurrants, for example. This aphid is rarely dangerous for plants. It also affects oleanders.

The damage caused

In the garden, when a severe aphid infestation occurs, the following is generally observed:

- a slowdown in growth,

- deformation of leaves,

- the development of sooty mould, a disease characterised by the appearance of a black, sticky substance on leaves and fruits,

- a decrease in fruit production,

- an increased risk of diseases as aphids, by piercing plants to feed, can transmit numerous viruses such as cucumber mosaic virus, for example.

Mechanical control

The first method to combat aphids is mechanical control. It involves:

- dispersing aphid colonies using a water jet (hose or sprayer),

- crushing aphids by hand… which is slow and tedious!

For fruit trees, using a glue ring placed around the trunk and on the tree’s stake is often recommended. This device, designed to mechanically trap ants, also captures other beneficial insects. Do not overuse it, and if you use these glue bands, only leave them in place from April to June.

Natural aphid treatments

Auxiliaries are not always present in sufficient numbers to control aphid populations, and in cases of massive outbreaks, several solutions are available to you.

Act gradually, depending on the severity of the attack, by spraying:

- A solution of black soap at a rate of 15 to 30 g per litre of water, at the first signs of attack.

- An insecticidal product based on plant pyrethrum, as a last resort.

- On fruit trees, apply a whitewash based on lime to the trunk and main branches in the winter following a year of heavy pest invasion (and not systematically every year or every two years). This helps to largely destroy overwintering forms of aphids, but not only.

Before anything else, we advise you to check beforehand for the presence of beneficial insects (larvae or eggs) on the plant. Black soap, whitewash, and insecticides are not selective; they will also kill beneficials.

Some gardeners also use infusions of garlic pods, decoctions of wormwood or tansy, or even peppermint manure. However, at present, their effectiveness has not been scientifically demonstrated.

Biocontrol solutions

It is possible to purchase certain beneficials from garden centres or online to introduce into the garden to combat pests. For the amateur gardener, introducing a beneficial is delicate: it is essential to choose the right species, the one best suited to the problem at hand, to introduce it at the right time and in the appropriate quantity.

This solution is particularly well-suited for greenhouses or conservatories. For example, at Promesse de fleurs, it is the larvae of lacewings that work effectively in our greenhouses.

On the left: lacewing larva (photo by Christian Pinatel de Salvator via Wikipedia) – On the right: adult lacewing

The beneficials introduced into a garden will only remain and survive if they find all the conditions favourable for their development throughout the year. Otherwise, they will die or leave. It goes without saying that after introduction, the use of any chemical or organic products (insecticidal, sulphur, black soap…) should be avoided.

In a garden, it is much more effective, sustainable, and less costly to attract the native beneficials present in the environment by installing shelters or insect hotels.

Prevention

The best prevention against aphid invasions is to create a biologically balanced garden. Indeed, although it may be surprising, aphids are useful in the garden as they serve as a food source for beneficial insects that, well-fed throughout their life cycle, are more numerous to effectively combat pests of fruits and vegetables, which are the plants that truly need protection. Reducing their population is fine… eradicating them, no! So, leave some aphids on ornamental and wild plants.

Colony of black aphids on elder (Sambucus nigra)

Note that the development of aphid colonies is often a sign of excessive plant vigour and an imbalance in the composition of the sap. Avoid excess nitrogen-rich fertilisers.

Virginie’s opinion: Personally, I do absolutely nothing! I wait; the predators: ladybird larvae, hoverflies, lacewings, small parasitoid wasps (Aphidius), and even great tits will arrive and clean up. At first, there may be a lot of aphids, and it’s hard to do nothing, but the more you treat, the more you’ll have to treat, and even black soap is not harmless as it is non-selective; it also kills beneficial insects. You need to wait about 2 to 3 years for the biological balance to establish itself, and then it regulates itself.

To create a good balance in the garden:

- Plant ground covers that provide shelter for beneficial larvae, particularly ladybirds.

Ladybird larva enjoying a meal.

- Early in spring, plant a bed of phacelia and borage in the vegetable garden, which will bloom from early June. These flowers attract hoverflies, which are predators of aphids.

- Encourage the permanent presence and winter survival of beneficial insects so they can intervene as early as possible in spring and curb outbreaks: hoverflies, ladybirds, lacewings, micro-wasps, gall midges, great tits, and earwigs by installing shelters, insect hotels, and nesting boxes.

The great tit delights in aphids.

- Plant plenty of flowers around the vegetable garden and among the vegetables, and leave “trap” plants infested with aphids (chamomile, nasturtium, foxglove…).

- Subscribe!

- Contents

Comments