Hardy plants and hardiness

Definition, tips and practical cases

Contents

Hardiness, according to the definition from French dictionnary Larousse, refers to a plant’s or animal’s ability to withstand harsh living conditions. In gardening terms, this qualifier has evolved to mean the ability of a plant to resist cold and frost in a given region.

This concept, often misunderstood, can sometimes lead to failures in the garden, as a plant deemed hardy may not withstand the same conditions in every garden. We therefore propose to clarify this notion, its relative nature, and explore the various factors that influence the cold resistance of outdoor plants.

Hardiness, definition

Hardiness is an assessment of a plant’s resistance to cold. This assessment is more or less subjective and depends, in the garden, on numerous factors such as exposure, soil type, moisture, intensity, and duration of the cold…

For gardeners, a plant’s hardiness is a concept that arises from various cultivation experiences and observations made in the field.

There are, in fact, several levels of hardiness. Typically, a plant is said to be:

- Very hardy if it survives without damage at temperatures below -15 °C.

- Moderately hardy if it can endure temperatures down to -10 to -12 °C,

- Not very hardy if it dies below -5 °C.

However, these temperatures should be taken as indicative; they do not hold the same value depending on whether you are gardening in Perpignan or Charleville-Mézières!

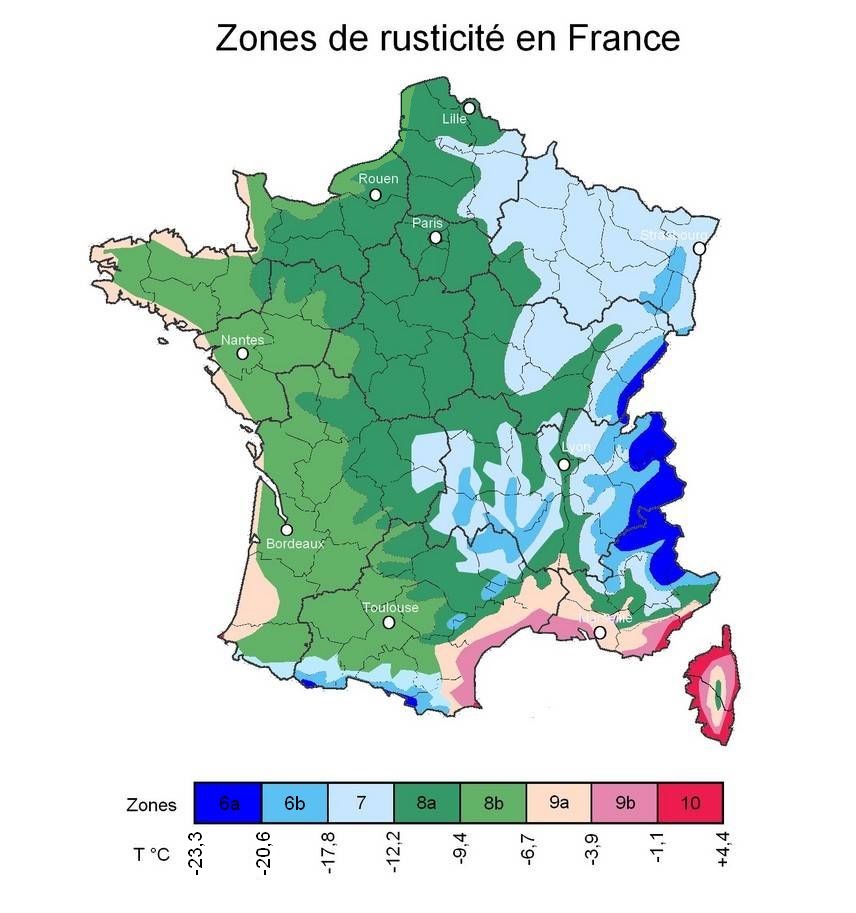

Indeed, a plant’s hardiness also largely depends on the climatic zone in which it is cultivated. These climatic zones are represented on a map divided into USDA geographic zones. A USDA zone is a geographical area that corresponds to a climatic region in which a category of plant can live, meaning it can withstand the minimum winter temperatures of that zone.

In the garden: the factors that influence hardiness

The hardiness of a plant is an indicative data point, and many factors other than just cold can influence its resistance.

The plant’s exposure to sun and wind

- The sun warms the soil and plants. Morning sun (exposure) promotes rapid warming of the vegetation. When the stems and buds (or leaves in evergreen plants) are frozen, a too-rapid thaw can destroy plant tissues by causing them to “burst”, leaving them no chance to regenerate. In contrast, a northern, southern, or western exposure, as well as the shelter of a tree or hedge, will allow the plant to warm up slowly, limiting frost damage. Northern exposure limits drastic temperature changes between day and night, while a southern wall tends to release some of the heat it absorbed during the day at night.

- The wind significantly affects the “felt” temperature. We often experience this, as do plants, particularly their aerial parts which are sensitive to icy winds. In winter, wind doubles the effect of cold by lowering the temperature by several degrees, drying out the air and plants, and breaking evergreen leaves or stems laden with buds.

- The nature of the soil is an essential factor for a plant’s hardiness: indeed, roots continue to live underground while the aerial vegetation seems dormant in winter. Just imagine them trapped in a block of ice to understand that they can no longer perform their essential function. Asphyxiated and deprived of oxygen, they are, for example, unable to absorb the water and nutrients essential for the plant’s survival. The more draining and permeable the soil (gravelly, sandy, light) the quicker it evacuates water, making it impossible for the roots to freeze. In contrast, heavy, compact, “sticky” soil rich in clay traps water for a long time and constitutes an aggravating factor of cold in case of severe frost.

=> The choice of location is very important: planting in a hollow that collects runoff water from rain will promote soil waterlogging, and thus the formation of ice blocks at the roots. Meanwhile, planting in a raised bed, on a slope or incline, will allow water to drain more easily and limit its penetration into the ground.

=> Finally, a stony soil will warm up much faster than clay soil.

- The duration of the cold episode is a determining factor, at least as much as the lowest recorded temperature. A brief but intense frost (for example: a few hours at the end of the night, followed by a rise in temperatures above zero during the day) will not have the same destructive impact as ten days without thaw, which will allow the soil to freeze several centimetres at the root level. The “hardening” of plants, depending on the more or less sudden arrival of cold, also greatly influences their sensitivity to frost. Gardeners also note that severe late-winter frosts, occurring when vegetation is ready to restart, cause much more damage than frosts of the same intensity that occur in the heart of winter when plants are dormant.

- The age of the plant also significantly affects its ability to withstand cold. An adult plant grown in the garden for at least 3-4 years will cope more easily with climatic hazards than a young plant recently planted. The older plant will have developed a deeper, more substantial root system, filled with reserves and therefore more capable of withstanding difficult conditions. A mature bush or tree will have thicker branches and bark, providing good protection against the cold. Its ability to develop new so-called dormant buds may also, in some cases, allow it to regrow from the stump or even from the base of the branches after being damaged by the cold.

- The timing of planting should also be chosen carefully, depending on the severity of winter in each region. Depending on whether one is in Lille, Strasbourg, Brest, or Marseille, one does not necessarily plant at the same time of year. In our coldest regions, it is preferable to plant in the ground in spring, as soon as the frost ends: they will have several months to gain strength and settle before the arrival of cold. This recommendation remains valid for all those planted in hardiness zone limits, for example when planting a strawberry tree, hardy to -12/-15°C in the Paris region (zone 8, minimums -12/-15°C). Meanwhile, conversely, one would plant in autumn in mild regions subject to dry summers.

- Rain, or rather the regularity and abundance of winter precipitation, plays an important role in hardiness. Just as draining soil allows water to “drain” deep, dry soil in winter can increase cold resistance by a few degrees. For some bulbous plants, for example, the bulb fears permanent moisture more than cold itself. The same goes for plants from semi-desert climates that will withstand a few degrees of frost, but in very dry soil. Some alpine and high mountain plants survive low temperatures thanks to the protection of a thick blanket of snow, which insulates them from both cold and moisture.

- Container cultivation outdoors increases the fragility of plants to cold: the volume of soil is reduced, and the entire surface of the pot is in direct contact with frost. This promotes the formation of ice all around the roots.

Improving a plant's hardiness

If the hardiness of the plant you have chosen is “a bit marginal” for your region (see the climate map below), you can enhance its cold resistance by implementing various protections. Indeed, to provide better conditions for them, you can take action on several levels:

1) Choose the right exposure:

- For the most delicate plants, select the least cold areas of your garden in winter (objectively identified using a thermometer), such as a south-facing wall.

- Exclude cold-sensitive plants from areas exposed to prevailing winds, especially if they come from the north or east. The shelter of a hedge or a grove of evergreens is often a good refugium for the less hardy plants, just like the walls of a house or garage. Depending on each plant’s sunlight requirements, provide them with a north (where temperature fluctuations are moderated), west, or south exposure, while avoiding east.

2) Improve drainage:

- If your soil is heavy and damp in winter, mix a good amount of gravel, pumice, and leaf compost into your garden soil.

- Plant on a “mound,” on a slope, or in a raised bed of 20 to 30 cm, on a bank, or in a large rock garden.

3) Limit the effects of cold by protecting your plants:

- Place a thick mulch of straw or fern fronds at the base of the plant, for example. This “mattress” will insulate the soil from the cold while limiting water infiltration at the plant’s stump if positioned correctly. You can also, in some cases (on perennials or bulbs, for example), place a waterproof cover (plastic tarp) over this mulch to keep the soil dry in winter, but only if the plant requires it.

- Gather the stems and tie them loosely to protect the heart of the plant (grasses, perennials, or cold-sensitive evergreen shrubs).

- Surround the plant with a double-layer winter cover, which can easily provide an additional 2°C, mainly through a windbreak effect. It should preferably be placed on the lower part of the vegetation if it is already well developed. Ventilate during the day if temperatures rise, to allow this protected plant to breathe.

Remember that the harsher the climatic conditions, the more care must be taken with planting according to each plant’s requirements, and the quicker it must be acclimatised to your garden before winter arrives.

Choosing Plants According to Hardiness Zones

Hardiness Zones in France:

Originally created in the USA by the Department of Agriculture, hence the name USDA, these zones are represented on a map. They are established based on the averages of the minimum temperature recorded over approximately 20 years. These zones are numbered from 1 to 11. Each zone is subdivided into a and b based on an approximate difference of 2.78 °C.

In practice, to determine which plants are hardy in your garden, you can adjust your hardiness zone positively (by gaining a few degrees) or negatively (by losing a few degrees) based on various factors we have detailed above.

A few examples:

It can be considered that if your soil is clayey and heavy, you lower the climate zone by “one notch”: your garden located in zone 8a (-12.2°C to -9.4°C) will be better suited to plants from zone 7b (-15°C to -12.2°C), which can withstand -15°C rather than -12°C. A rose bay, for example, will have little chance of surviving the winter in this garden.

Conversely, if your garden, still located in zone 8a (-12.2°C to -9.4°C), has sandy soil (very well-drained), you can consider that a plant from zone 9a (-9.4°C to -6.7°C) will have a good chance of surviving the winter at your place: you can attempt to grow the rose bay, but also Grevilleas, which are slightly less cold-resistant.

This mapping, while a precise indicator of minimum winter temperatures, does not take into account other factors that significantly influence a plant’s adaptation to a particular climate zone: certain specifics such as the nature or moisture of the soil and exposure to wind are not considered. Thus, sites with the same winter minima, but over very different durations, will be classified in the same zone.

The sheltered exposure parameter (no wind, against a south or south-west facing wall) also allows for a “gain” of about 2°C of warmth. The two parameters “very well-drained soil” and “sheltered exposure” positively combine for the plant, making it possible for you to attempt to grow a plant from zone 9a (-6.7°C to -3.9°C) in your very sheltered garden located in zone 8a, for example, a Cape Plumbago. These few degrees more or less make all the difference!

Climates in France:

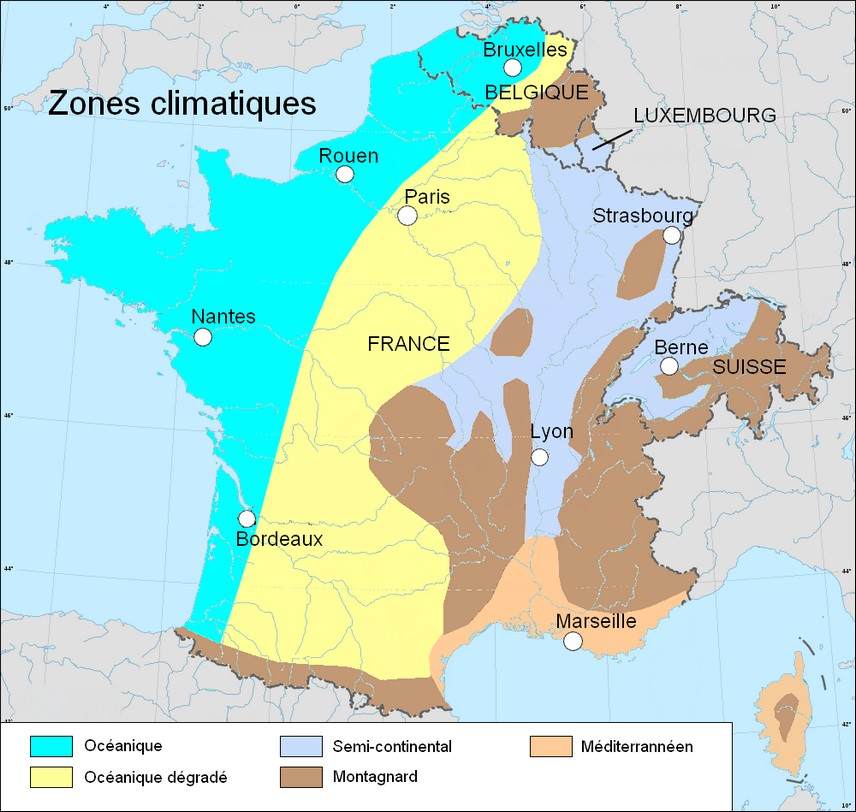

Metropolitan France generally enjoys a temperate climate. However, several types or sub-climates can be distinguished, with notable variations.

- The oceanic climate: characterised by relatively mild winters and rather cool summers, with frequent rainfall distributed throughout the year.

- The semi-oceanic climate: located to the east of the oceanic climate, with still perceptible oceanic influence, but diminished. Rainfall is lower, winters are less mild, and summers are less cool.

- The montane climate: well-watered by rainfall, the reliefs “catch” the clouds that cool as they rise in altitude and lighten by releasing precipitation. Temperatures vary according to altitude (approximately 6 °C is lost every 1000 m).

- The Mediterranean climate: this is the climate of regions bordering the Mediterranean. Rainfall is uneven from year to year, irregular, few in number but intense (mainly in autumn), and summer is hot and dry for two to three months. Winter is relatively mild, but colder inland than on the coast. The degraded Mediterranean climate (known as the olive climate) extends up to Montélimar, while the true Mediterranean climate of the Côte d’Azur (known as the orange climate) rarely experiences frost in winter.

- The semi-continental climate experiences harsh winters and hot summers. It will be less “watered” (dry semi-continental) if a mountain range blocks humid air masses coming from the ocean, or more so in the opposite case (humid semi-continental climate).

As we have seen earlier, these data can be adjusted based on the specific situation of each garden and each area of the garden.

An orange tree in the soil of Maubeuge, is it reasonable? Some practical cases

If we were to take a few examples of plants suited to each of our regions, we could, based on simple observation of nature, choose without error. But the gardener is curious, and this lover of exotic challenges often succumbs to heartthrobs…

- In Alsace, the Ardennes, Clermont-Ferrand, and Lille (USDA zone 6 to 7), it is advisable to avoid planting a Callistemon, a Grevillea, or a Laurier-rose in open ground, unless you have an extremely sheltered patio in the city. These plants can withstand a few degrees of frost, but not -15°C for eight days in wet soil.

- Chinese roses (Rosa mutabilis, Rosa Old Blush), some botanical roses (Rosa moschata the musk rose) or hybrids of Rosa sempervirens (Felicité et Perpetue) and Rosa bracteata (Mermaid) are more sensitive to cold than others. Capable of withstanding -12 to -15°C, they can still be grown without difficulty in zones 8 to 9, or even 7b depending on the specifics of your garden, meaning in many regions, outside continental or montane climates.

- Lavender, rosemary, and cistus, tied to Mediterranean landscapes, are often sufficiently hardy to endure -12°C occasionally, or even more. However, they are truly viable only in what is known as the olive zone, with a short winter, no excess moisture, occasional frosts, an early spring, and in very well-drained stony soils. If your zone 7 or 7b garden offers them the best conditions, you can attempt to grow them. But if you plant them in waterlogged, heavy soil in your zones 8 and 9 garden, they will perish due to the combined effects of frost and moisture.

- Agaves, and more generally “cacti”, from semi-desert zones, require very dry soil in winter to withstand frosts. In France, no climatic zone is characterised by very dry winters: theoretically capable of withstanding -8°C or even more, they can only be successfully grown in open ground in zones 9a, 9b, and 10 (down to -5°C at the lowest). However, they will thrive almost anywhere in a pot filled with sandy substrate, sheltered from rain in winter, under a roof overhang, for example.

- The stunning bougainvilleas and orange trees, on the other hand, are only truly viable in open ground in a narrow strip of the southern Mediterranean or Atlantic coast, where it rarely and lightly freezes. These are zone 10 and 9b plants exclusively. If you have a large greenhouse that serves as an orangery, kept just above freezing, there will be no problem regardless of the region!

After this somewhat didactic overview of the many factors that influence a plant’s hardiness, it is up to each gardener to distinguish between the dream of exoticism, which is legitimate, and the reality of the terrain, which holds surprises. Numbers, when talking about plants, and therefore living beings, cannot constitute absolute truths. Every garden is different. You discover enclaves of warmth or unsuspected cold traps. For example, place thermometers in various locations for a whole winter or two before attempting the adventure of fragile plants. Take the time to observe the soil in your garden, to understand the wind. Also, look at what grows in your neighbours’ gardens, and try to benefit from their experience. Before choosing their location, physically put yourself in the place of a “frost-sensitive” plant on a grey, cold winter’s day. Perhaps more than the numbers, this experience allows you to detect the spot that will be most favourable to it.

To go further

- Discover more on the subject in our advice sheet: How to determine the hardiness of a plant?

- Subscribe!

- Contents

Comments