Plant galls: what are they?

Anyway, it's not a big deal!

Contents

Strange growths, swellings on a stem, coloured balls or protuberances… There are countless different galls, and it would be difficult to list them all. A gall or cecidium is not a disease, but a reaction of the plant to the sting of an insect or mite (in the vast majority of cases) that lays its eggs within the very tissues of the plant. This tissue reaction will create “abnormal“, deformed, and sometimes spectacular parts on the plant. This gall will then serve as protection and food for the parasitic organism. But a gall on my plant: is it serious, doctor?

How is a gall formed?

A gall or a cecidium (the more scientific term) is the result of a plant’s reaction to the presence of a parasitic organism (less commonly symbiotic) within it. This parasite can be a fungus, a virus, a bacterium, a nematode, but is most often an insect or a mite: the resulting gall is then called a zoocecidium.

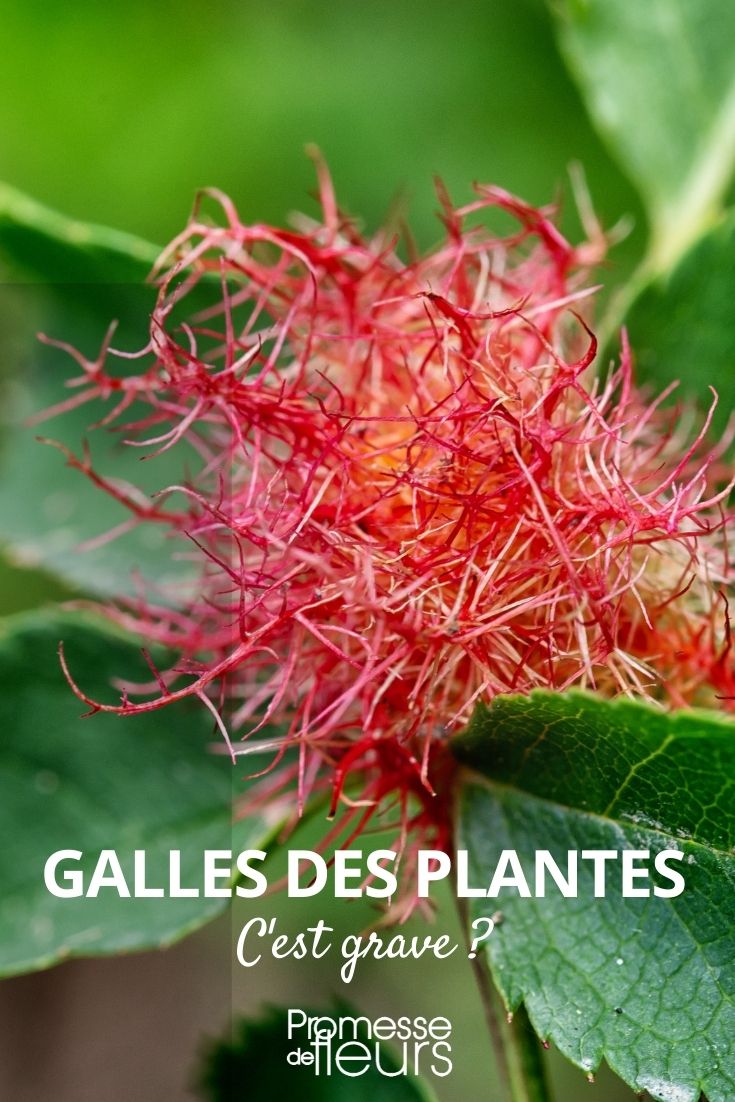

The parasite secretes a series of chemical compounds that radically alter the development of certain tissues of the host plant. This creates abnormal growths, more or less large lumps, organ deformations… akin to “benign tumours”. These deformities, sometimes barely visible to the naked eye, can conversely be very colourful and even aesthetically pleasing at times (for example: the bedegar on Rosa sp.).

A gall or cecidium can be found on various parts of the plant: stems, leaves, buds, roots, or fruits. A gall actually provides “shelter and food” for one or more larvae of insects or mites: the transformed plant cells serve as nourishment as well as protect the larva from external threats (predators, parasitism, humidity, cold…).

The study of galls is called Cecidology and the naturalist or biologist who studies them is therefore a cecidologist. It goes without saying that cecidologists are few in number, and if you feel inspired to embark on this adventure: don’t hesitate!

Please note: A gall should not be confused with scab. Scab is a disease in humans and animals, but by analogy, it is also the name of some cryptogamic and bacterial diseases in potatoes such as silver scab, cork scab, or powdery scab.

Hairy gall of the rose</caption]

Hairy gall of the rose</caption]

What to do if you spot a gall on a plant?

Do nothing! It is not a disease, but a reaction of the plant to a parasite.

This is in no way dangerous for the plant. The “damage” is purely aesthetic. At most, one might observe a slight decrease in vigour when the galls are so numerous on the leaves that they reduce photosynthesis.

This type of parasitism is advantageous for the parasite, of course, and should, in theory, be disadvantageous for the plant. However, the host plant seems to cope well with this parasitic attack. According to recent research, if the plant copes well, it is due to its cellular differentiation (the gall itself). Thus, the plant manages to “duct” the parasite, limiting it within this gall. In other words, the creation of a gall is a protective reaction of the plant itself.

Gall Pediaspis aceris on maple leaf

Which plants are affected?

A great number of plants can be “affected” by galls: trees, shrubs and bushes, perennials, and even annuals or vegetables. It is therefore very difficult to describe them all, and even more complicated to attempt to make generalisations about recognising a gall.

The most famous and recognisable are:

- The oak galls (as there are several types) or oak apples: round balls located in the axil of the leaves, caused by insects, particularly Cynips;

- The bedegar or hairy gall on roses and briars: a kind of mossy ball caused by a tiny wasp, the rose Cynips;

- The horned gall of the lime tree: small bright red spikes located on the leaf, caused by mites;

- The pineapple gall: which deforms the tips of the branches of the Norway spruce, caused by an aphid;

- The beech gall midge: small pips on beech leaves, caused by a tiny dipteran.

Galls on oak, lime, and beech

Galls on oak, lime, and beech

Each gall or cecidium is named after the organism (insect, mite, virus, bacterium, fungus…) that causes it. Thus, the famous rose gall, called bedegar (sometimes spelled ‘bédéguar’ in French), caused by a small hymenopteran, Diplolepis rosae (or rose Cynips), will be named: Diplolepis rosae.

Each species of insect or mite will only parasitise a single species of plant (more rarely a genus). This is why the (rare) identification guides for galls are primarily organised around a botanical classification. In other words, one must be able to recognise the plant with certainty, find it in the guide before being able to form an idea of the possible parasites. Therefore, a good understanding of botany is essential before delving into cecidology. A science that ultimately serves as a bridge between botany and entomology (the study of insects and other terrestrial arthropods).

- Subscribe!

- Contents

Comments