Do you have a barometer at home? I would be curious to know the answer, as this little object seems almost from another time in the age of digital weather stations and various online forecasting sites, which provide us with so much information at the click of a mouse...

Personally, I just retrieved one from my father-in-law, who often consulted it, and I wanted to keep it to remember him, but also my grandfather, whom I still see tapping the curved glass to, as he told me, update it.

This made me want to learn more about this vintage object and share it with you in this little mood piece.

The barometer: where does it come from and how does it work?

The word barometer comes from the Greek baros, meaning weight. It is an instrument that measures atmospheric pressure. While modern weather data informs us about various variables such as air temperature, wind strength and direction, or humidity (the degree of moisture in the air), it also allows us to know atmospheric pressure thanks to this instrument that is almost as old as time itself. Variations in this pressure tell us a lot about the weather for the coming days. Judging by the number of barometers sold on a well-known second-hand site, and those found at car boot sales, many people seem to discard them. An essential tool for weather enthusiasts, as they allow for the assessment of surrounding atmospheric pressure in a specific location, barometers have nonetheless served generations of gardeners. Let's take a little trip back a few centuries...

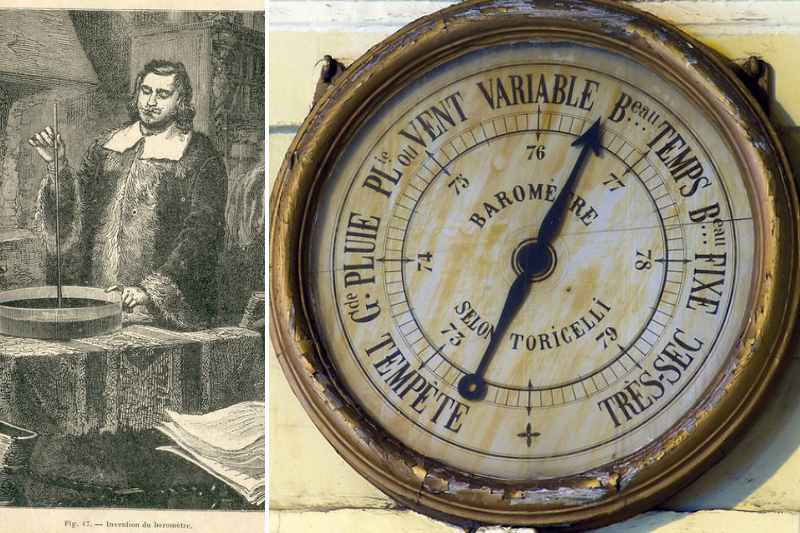

The Invention of the barometer

A few years before the birth of the barometer, the thermometer made its appearance in a "modern" form as early as 1621 with Cornelis Drebbel, a Dutch physicist. This was a significant step for gardeners of the time, who could better manage extreme temperatures on plants, during a period when research was progressing considerably, particularly with the study of plant behaviour in the greenhouses that were springing up everywhere.

The invention of the barometer is associated with the name of Evangelista Torricelli, an Italian physicist who, in the 17th century, conducted in-depth research to measure air pressure. He built upon Galileo's water pump idea, following an unresolved issue faced by the fountain makers of Florence who wanted to raise water from the Arno to the terraces of gardens. He highlighted the principle of atmospheric pressure: air has weight! And it is mercury, a liquid denser than water, that he used as a basis. At that time, his research had no direct meteorological interest, but in 1643, Torricelli thus created the first instrument capable of measuring air pressure, then called "weight of air". It consisted of a mercury column tube (the famous "quicksilver"), which expressed this atmospheric pressure in millimetres of mercury (mmHg). This measurement would later be called hectopascal, in honour of Pascal, the philosopher and scientist who demonstrated that the height of mercury, linked to the weight of air, decreases with altitude. The Academy of Sciences would only give the name barometer to this major discovery in 1676.

The evolution of barometers: a story with many layers

The history of the barometer has undergone many evolutions before reaching us. It is mainly in the second half of the 17th century that discoveries began to unfold.

In England, the observations of Robert Hooke, an English physicist, a versatile scientist, and Robert Boyle, an Irish physicist, allowed them to advance on the air pump in the 1660s. They had the idea to bend the barometric tube upwards, thus creating the siphon barometer, still used today. Robert Boyle was also the first to use the term barometer across the Channel, as early as 1665, and to establish a graduation system.

Water barometers appeared a few years later, around 1793, but were quickly abandoned due to their unreliability.

After the novelty of the mercury barometer, the measuring instrument was refined around 1800 thanks to Jean-Nicolas Fortin (1750-1831), a French engineer in the service of King Louis XVI: he managed to create a sort of portable barometer, with a foldable tripod, as the barometers of the time were not very manageable.

Then in 1818, another Briton, Alexander Adie, invented the gas barometer: he enclosed a volume of gas that changes with air pressure. However, like the water barometer, it proved to be insufficiently accurate.

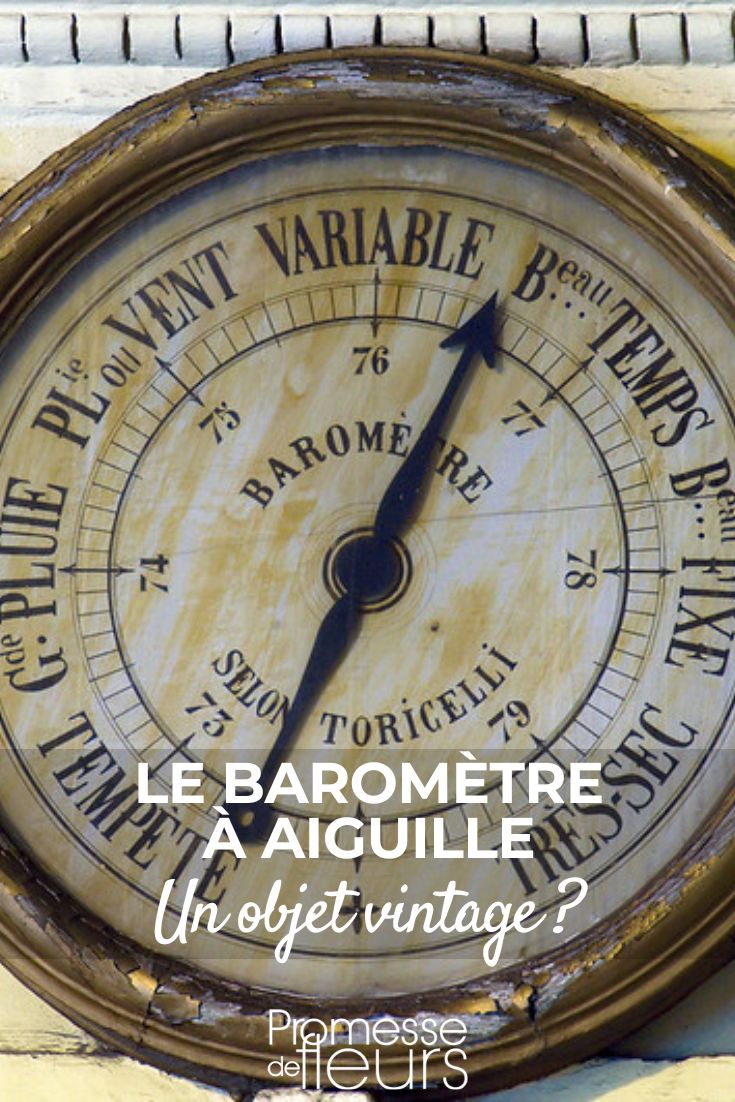

A notable improvement came from Lucien Vidie, an inventor and French physicist, in 1844. He invented what would be known as the Vidie capsule, better known as the aneroid barometer, or the dial and needle barometer. This barometer consists of a hermetic wall and contains a vacuum. Atmospheric pressure exerts pressure on the box, which is pushed by a spring, causing the needle to move on the dial. This same barometer would later be adapted by Eugène Bourdon, a French engineer and clockmaker, in 1849, to create a tube manometer (the Bourdon manometer), allowing for pressure measurement in various everyday applications (heating, tyres, piping, etc.).

It is the aneroid barometer that has gradually been improved, becoming increasingly accurate, leading to the one we know well today.

How to use it? How to read a needle barometer?

The local atmospheric pressure causes the needle to move to one side or the other of the dial. It is the direction of the needle's movement that matters in the barometer, not the needle itself, and it indicates the trend towards dry or rainy weather for the coming days. A reference needle, which is updated, allows for observing the variation of the moving needle from one day to the next.

Graduated from 945 hPa (hectopascal) to 1082 hPa, it is now understood that a depression system (low pressure) varies towards an anticyclonic system (high pressure) starting from 1013 hectopascals, which corresponds to the middle of the dial. When the needle moves to the left, indicating that atmospheric pressure is dropping, the weather is likely to turn bad (rain to storm). Conversely, when the needle tilts to the right (upwards, indicating that atmospheric pressure is rising), the weather is likely to be fine (sunshine and corresponding temperatures). The barometer can also be used to roughly determine altitude.

Note: always calibrate your needle barometer before using it daily, or when changing regions: this update (calibration) involves turning the small adjustment screw at the back until the needle is positioned on the day's atmospheric pressure (to be checked on your local weather site such as, in France, Météo France or Météo Agricole, for example). Raise it slightly if the trend is downward, or lower it if the trend is upward. Tap the glass to free the needle and adjust for play, and you're good to go!

Endless models...

Like in the field of horology, the barometer has adapted to our lives, and alongside the charming old brass cases, there are now next-generation barometers, revamped or even futuristic: potassium crystal barometers (a legacy of the FitzRoy barometer), water barometers, up to digital weather stations, in all shapes, from large beautiful objects to hang in your home to pocket barometers. Some are usable at very high altitudes. A few companies have even acquired genuine expertise and continue the tradition of mechanical barometers of yesteryear, such as the Naudet company, certified as a Living Heritage Company. And of course, there are all the humorous and regional barometers found in our French countryside, like the Ardèche barometer, as well as the Breton barometer in the shape of a pebble or the montane version in the shape of a pine cone...

Since I installed a barometer at home, I find myself passing by it every morning, and not a day goes by without me glancing at it, updating the reference needle to see how it varies! And you know what? It never gets it wrong!

And you, what is your relationship with this little object? Share your story or anecdotes with your barometer, perhaps even your collection of barometers, as these retro objects can inspire collector's passions.

Find much more detailed and technical information in A Brief History of the Barometer, on the website Culture Sciences Physiques, as well as on the French site Météo Vintage!

Comments