Leaf shapes: how to recognise them?

Knowing how to recognise foliage to better integrate them into the garden

Contents

The plant world offers us an incredible variety of shapes in foliage, making each tree, bush, grass, or small perennial unique and recognisable. Initially classified according to their position on the stem as opposite or alternate leaves, the leaves exhibit ovate, round, or more or less lobed laminae, palmate, and sometimes even perfectly cylindrical, as seen in water lilies, for example. Just like the shapes of flowers, the botanical dictionary has a rich and very specific vocabulary dedicated to them, which I invite you to explore in this article that is entirely devoted to them!

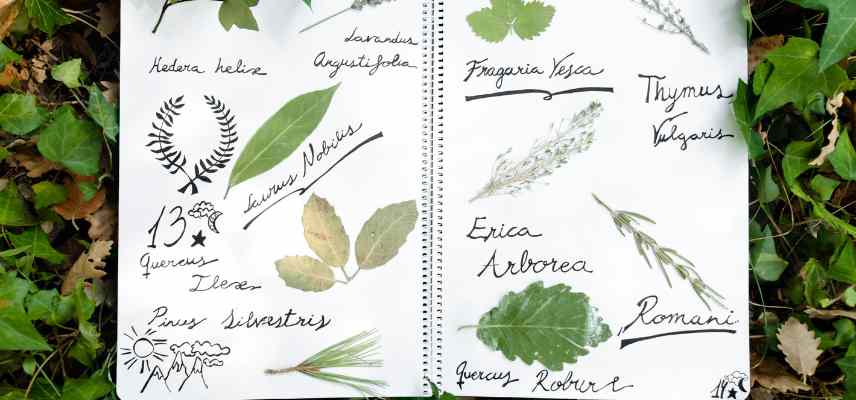

Creating your herbarium is stepping into the wonderful world of leaves, all so different!

Recognising a leaf

A plant species can be recognised by the shape of its foliage, which often catches our attention. However, the leaves that make up the plant encompass a much broader anatomical complexity. In this article, we will only discuss the shape of the lamina, which is the dominant, flat, and broad part, although leaves actually possess other characteristics unique to each species that help refine their identification or spot species or varieties, including:

- whether they are simple (a single lamina like that of lilac) or compound (composed of several leaflets, pinnate or sometimes bipinnate, like the leaf of mimosa): this is the first key to identification in botany.

- their position on the stem and relative to each other, opposite (facing each other, two leaves at each node) or alternate (a single leaf at each node), to mention just the two most common: this is referred to as phyllotaxy, which is the second key to identification.

- their mode of attachment to the stem, which helps refine recognition: often petiolate attachment, but also sheathing, perfoliate, sessile (without a petiole), and many others…

- the shape of their margins: the edges can be entire, dentate, incised, undulate, crenate, spiny, sinuate, ciliate, etc.

- their nervation, meaning the shape and position of their veins (botany employs about fifteen astonishing qualifiers such as campylodromous, parallelodromous for parallel veins, palinactinodromous, etc.)

- their colour, ranging from green to bronze and blue, including purple, red, or black.

- but also their size, the length of the petiole, their texture glabrous or downy, etc.

The shape, which is our focus in this subject, generally provides a clue about the species of a plant. It is an important marker in plant morphology and in the classification of species. It often lies midway between two forms, depending on the species or the stage of leaf development (basal or upper leaves). We will review them below.

Read also

Trees and bushes with large leavesThe ovate leaves

Just in terms of leaf morphology, there are around forty different shapes, each with its own set of descriptors, highlighting the diversity of the plant world! Among these, many resemble each other, and numerous ones exhibit subtle variations.

Without listing them all here, I have grouped leaf shapes into major “families” and selected the most classic or identifiable ones for clarity in this vast foliar universe. To start, here are the most common ovate leaves, which can be distinguished as follows:

Ovate leaves

Leaves shaped like an oval, wider in the middle. A large number of leaves can simply be described as ovate.

Some examples: holly (with a dentate margin), Magnolia soulangeana, Malus sp. (apple trees), Ficus elastica.

Holly, apple tree, and Ficus elastica</caption]

Holly, apple tree, and Ficus elastica</caption]

Elliptical leaves

This is an elegant variant of ovate leaves, where the shape gracefully tapers. These leaves, shaped like an ellipse, are wider in the middle and taper at both ends, resembling a perfect ellipse. The term “elliptical” comes from the Greek “elleipsis,” meaning ellipse.

Some examples: laurel (ovate), but also common jasmine, which tapers to a point, Aspidistra, Feijoa, etc.

Laurel, Aspidistra, and common jasmine</caption]

Laurel, Aspidistra, and common jasmine</caption]

Oblong Leaves

These leaves are elongated, almost parallel on the sides. Their oblong shape, longer than wide, is a classic among leaves!

Some examples: garden primrose, Sophora japonica, Aspidistra (between elliptical and oblong).

Obovate leaves

These are oval leaves shaped like an egg but inverted, with a narrower base and a generously rounded wider apex.

Some examples: Magnolia, Bergenia, Peperomia obtusifolia.

Lanceolate leaves

Shaped like a spear or sword, these leaves taper to points at both ends, adding dynamism to the lamina. Their base is slightly wider than the apex. They can be found in certain bulbous plants, many perennials, and shrubs.

Some examples: olive, Eleagnus, Pyracantha, walnut, Sansevieria, Yucca, Crocosmia, and many ferns like Dryopteris or Matteucia are also classified as lanceolate.

Hesperis matronalis, Dryopteris, and Cotoneaster</caption]

Hesperis matronalis, Dryopteris, and Cotoneaster</caption]

Spatulate leaves

These leaves are generally elongated and oval but are rounded at the apex (top of the lamina) and gradually taper to the base towards the petiole. These leaves resemble the shape of a spatula (the term spatuliform is also used). This can be solely the juvenile form of the leaf.

Some examples: Ajuga reptans, Corokia.

Round leaves

These are leaves with more or less circular shapes, which take on specific qualifiers:

Orbicular leaves

This is the botanical term for leaves that are almost perfectly circular. Their orbicular shape comes from the Latin “orbis,” meaning circle or sphere. These leaves are unique and a model of perfection in the plant world. They are often peltate (peltata), meaning that the petiole is attached to the middle beneath the surface of the lamina (and not at its base as is the case with most leaves). They sometimes resemble cordate leaves.

Some examples: Venus’s navel (Umbilicus rupestris), Asarum, or Pilea.

Umbilicus rupestris, Asarum europaeum, and Pilea peperomioides

Circular leaves

They are all round! Like the Nymphaeas or water lilies, the lotus (Nelumbo nucifera), or garden nasturtium. Their edges are sometimes undulate as in the nasturtium, dentate or crenate in Darmera peltata and Saxifraga stolonifera, or shaped like a pie server in the giant Amazonian water lily.

Nasturtium, lotus, and Victoria amazonica

Reniform leaves

Literally kidney-shaped (from the Latin reniformis), these leaves add a touch of originality with their rounded contours and distinctive notch. Their lamina is recognisable by this astonishing shape reminiscent of a tractor seat.

Examples: Farfugium japonicum, Petasites, and Asarum.

Petasites, Asarum, and Farfugium

Read also

5 large-leaved perennialsHeart-shaped or cordate leaves

It is also a subcategory of round leaves, with this small difference that adds to its charm. Here, the base of the leaf is attached in two rounded lobes to the petiole, and the pointed shape at the top of the leaf gives these leaves their name, reminiscent of the shape of a heart. “Cordata” indeed comes from the Latin “cor, cordis,” which means heart. This qualifier can be found in many species such as Tilia cordata.

Some well-known examples: Cercis sp., Houttuynia cordata, hostas, Colocasia (Taro), certain violets, Tilia cordata, Alnus cordata, Cercidiphyllum or the candy tree, Ipomoea, Cobaea, Dicentra, more commonly known as bleeding heart, Catalpa, Pothos, and Philodendron (Epipremnum) among houseplants… Note: The lilac leaf has a cordiform base but belongs to the ovate leaves, although it is tapered at its tip.

Pothos, Judd’s tree (Cercis canadensis) and Houttuynia cordata

Triangular leaves

These leaves are triangular in shape, as their name suggests. They are found mainly on certain poplars and birches and on some ivy (young leaf form not yet lobed), but also on Kalanchoe of Grémont.

N.B.: The so-called cuneate leaves are also part of these triangular leaves, which are much less common, however.

Populus nigra, Hedera and Betula

Narrow leaves and fine leaves

These are more or less tapered foliage, much longer than wide, sometimes with parallel edges, which take on different names:

Subulate leaves (subulata)

These leaves are very narrow and pointed, more or less long in the shape of a needle. Their subulate shape, from the Latin “subula” meaning needle, is one of the many examples of the fineness found in nature. The qualifier subulata is also found in certain species of Phlox, saginas, etc.

Sagina subulata (©Forest and Kim Starr) and Phlox subulata ‘Atropurpurea’

Linear leaves

They are long and narrow with parallel edges. Their simple and clean shape is one of the components of contemporary gardens.

Examples include those of bamboos like Fargesia, Carex (which resemble a gramineous form), Liatris (Kansas plume), or Cordyline.

Fargesia nitida, Carex oshimensis, and Cordyline australis

Lanceolate leaves

These leaves are very thin, lance-shaped, and tapered at both ends. They can be found, for example, in species of Mediterranean gardens, in plants that have adapted to dry climates by reducing their leaf surface area. Many trees or bushes exhibit leaves that are intermediate between lanceolate and oblong shapes (like the holm oak).

Some examples include many willows (basket willow, twisted willow, weeping willow), olive, holm oak, sweet chestnut, as well as persicarias, etc.

Olive, twisted willow, and sweet chestnut

Ribbon-like leaves

The lamina here is ribbon-shaped, long and flat, sometimes very flexible. These are the typical leaves of Clivia, Agapanthus, and certain Irises, etc. Commonly, we refer to sword-shaped or ensate leaves in Irises or Crocosmias, which are also considered lanceolate leaves.

Acicular leaves

In the shape of a needle, rigid, these leaves are typical of conifers. Their name, derived from the Latin “acus” meaning needle, reflects their fine shape ending in a point.

Examples include Pinus sp., Picea sp., Juniper, Larix, etc.

Juniperus, Cedrus deodora, and Pinus sylvestris

Palmate leaves

Palmatilobate and digitate leaves

These leaves are a subcategory of lobed leaves that I will not cover in full here due to their complexity. With lobes or segments radiating from a central point, and a palmate nervature, they resemble the shape of an open hand. The lobes extend beyond half of the leaf. They are both pinnate and lobed. There can be 3 to 5 main lobes, or even a dozen, and sometimes many more in palmate frond palms. Their name is derived from the Latin “palma,” meaning palm. We refer to digitate leaves when the leaf resembles fingers formed by the five lobes.

Some nuances can be found in leaves referred to as palmatifid, such as Tetrapanax: the divisions are less deep and only reach halfway through the leaf.

Examples include maples (Acer sp.), Liquidambar, plane trees, Hepatica (perennial), Fatsia japonica, Schefflera taiwaniana, heucheras, as well as Aconitum napellus, whose lobes are particularly deep and narrow like those of some Japanese maples.

Maple, Fatsia japonica, and Aconitum napellus

The original leaves

They are less common, but atypical and distinctive, sometimes even the only representatives of a genus or species!

— Labelled or flabelliform leaves: that is to say, fan-shaped like the unique ones of Ginkgo.

— Truncate leaves like the singular leaf of Liriodendron (tulip tree), also described as quadrilobate.

— Rhomboidal leaves, from the Greek rhombos, meaning spinning top, are diamond-shaped. They are also referred to as lozenge-shaped leaves, as seen in the Italian poplar.

— Sagittate leaves: the lamina of the leaf takes the shape of an arrow in certain tropical or aquatic plants (among others) such as Taro (Alocasia), water arrow (Sagittaria sagittifolia), Xanthosoma sagittifolium, Caladium, or Arum italicum.

— Hastate leaves: they resemble sagittate leaves, but are typically defined as resembling the blades of halberds. The term “hastata” is found in several species such as the hastate-leaved willow (Salix hastata) or hastate vervain.

Not to forget perforated leaves like Monstera deliciosa, although this term is not specific to botany.

Arum italicum, Sagittaria sagittifolia, and Alocasia

- Subscribe!

- Contents

Comments