If you buy potting soil commercially, there is a very high probability that it contains peat. Indeed, it is almost systematically integrated into substrates for its physical qualities, in terms of lightness and water retention. However, the widespread use of peat has a significant environmental impact! This involves the destruction of wetlands that are ecologically important. Fortunately, there are solutions to preserve them. Let’s take a look at the advantages of peat in the garden, the consequences of its use, and discover how to preserve this resource!

1- What is peat and where does it come from?

Peat is a fossil organic material that results from a slow accumulation of organic matter in an acidic, water-saturated environment that is very low in oxygen. These conditions prevent microorganisms, bacteria, and fungi from decomposing the organic matter, which therefore accumulates gradually. These particular environments are known as peat bogs.

As the organic matter is not decomposed, these environments are very low in mineral elements, leading to the development of specific fauna and flora. Many carnivorous plants (such as sundews and Sarracenia) can be found in peat bogs: they capture insects to supplement their nutritional needs, as they cannot draw nutrients from the soil, which is too poor.

Peat can take between 1,000 and 7,000 years to form. Therefore, it is not renewable on a human timescale. Ultimately, after a million years, the organic matter constituting peat bogs transforms into coal.

There are different types of peat:

- Blonde peat: it comes from sphagnum moss. It is relatively young (between 3,000 and 4,000 years) and fibrous. This is the layer that is found closest to the surface in a peat bog. It has an excellent water retention capacity, as sphagnum absorbs water. It is the most commonly used peat in horticulture and gardening.

- Brown peat: it originates from woody plants (trees, bushes), sedges, reeds, and Ericaceae. It is older (about 5,000 years) and found deeper down. It can also be used in the garden, although its use is less frequent.

- There is also black peat, which is older (up to 12,000 years). It is mainly used for wastewater treatment.

Thus, the darker the peat, the older it is.

2 - The advantages of peat in the garden

Peat has many qualities that plants need, to the point that it is difficult to replace. It is no coincidence that its presence has become almost systematic in marketed potting soils.

Peat acts like a sponge: it stores water and mineral elements, preventing the substrate from drying out too quickly. It has an excellent water retention capacity. Peat is therefore ideal for potted plants: as it stores water, watering can be spaced out or occasionally forgotten without the plants suffering too much. It is a particularly light and airy material that does not compact: thus, it is ideal for good root development. Indeed, in pots, the substrate can quickly tend to compact and suffocate the roots. Peat also has the advantage of providing a stable substrate that does not decompose or deteriorate.

Peat is particularly useful for substrates intended for repotting indoor plants, flowering plants for the terrace, etc. It is also widely used for growing carnivorous plants, as it perfectly matches their natural environment.

Dehydrated peat pellets are also available, used particularly for sowing. They swell as soon as they are rehydrated. Peat is also used to make biodegradable compressed peat pots.

3 - What problems are posed by the use of peat?

As peat bogs are very particular environments (acidic, saturated with moisture, low in oxygen), over time, a specific flora and fauna develop that cannot be found elsewhere. Many rare and protected species live in peat bogs and cannot adapt to other environments. These are mainly plants of wet and acidic soils. Sphagnum is very characteristic of peat bogs: it is a type of moss that absorbs water and tends to acidify the environment. It is the basis for the formation of peat bogs. In these wetlands, one can also find carnivorous plants, as well as Ericaceae, Cyperaceae, cotton grass, and reeds... Similarly, some plants (royal fern, molinia, Carex...) form tussocks: these plants grow on their old roots and dead leaves because these cannot decompose, thus forming clumps or micro-mounds.

In addition to their great biological diversity, peat bogs act as a true sponge... not only at the substrate or potting soil level, but the same happens on a regional scale. They limit the risk of flooding and also release water during dry periods. They play a crucial role in the hydrological balance of certain regions. Moreover, peat bogs store a significant amount of carbon (as they can be composed of 50% carbon), thus limiting global warming. They help regulate the climate on a global scale and also create cool microclimates. Peat bogs also have the advantage of filtering water: they purify it by removing various pollutants, thus acting as a natural purification station! The waters they release into the environment are therefore particularly pure.

Peat forms at a very slow rate of about 1 mm per year, or even less, which means it is not renewable on a human timescale. It takes thousands of years to form!

The importance of peat bogs is not "only" environmental; they also have a genuine historical interest. As peat forms very slowly and the material does not decompose, objects as well as plant or animal remains remain intact, allowing for a faithful tracing of a region's history. They are true archaeological archives! Human mummies in perfect condition, dating back thousands of years, have been found in peat bogs. Similarly, pollen grains are very well preserved in peat, allowing for the reconstruction of the vegetation and climate of a region thousands of years ago.

The exploitation of peat bogs is a true ecological disaster. They are drained and dried to extract peat. Generally, the soil then becomes dry and poor, and the typical plants of peat bogs will not be able to return.

The destruction of peat bogs is unfortunately not new. In the past, they were often considered useless and unexploitable environments, so they were drained to create agricultural land.

The figures are staggering: in France, half of the peat bogs have disappeared over the last 50 years. Fortunately, those that remain are now protected, which does not prevent the exploitation of peat bogs in other countries. Nearly 70% of the peat used in France for horticulture comes from the Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) or Ireland. Thus, the problem remains the same, as it is the peat bogs of these countries that are now threatened.

4 - Our tips and best practices to preserve this resource

Fortunately, there are alternatives to peat, with some materials having the advantage of being light and airy while retaining water and nutrients: these include coconut fibres, composted bark, wood fibres, and pine bark... Similarly, vermiculite is ideal for lightening the substrate. There are also patented substitutes that are real alternatives, such as Turbofibre® (conifer bark fibre, replacing blonde peat) or Hortifibre® (wood fibre).

If you are growing acidophilous plants, we recommend using composted pine needles or bark.

Leaf compost is also a good alternative to peat, which has the added advantage of being rich in mineral elements and microorganisms. You can make your own potting soil by mixing well-decomposed compost, garden soil, and coarse sand.

Today, there are more and more peat-free potting soils on the market, often composed of coconut fibres, bark, wood fibres... They are quite effective. For example, check out Père François Or Brun universal potting soil. or Ecolabel universal potting soil.

However, be wary of the "Organic" certification, which does not guarantee the absence of peat; on the contrary! Indeed, peat, by definition, is a natural and organic material, so it can very well be included in the composition of "organic" potting soils. Read labels carefully and analyse the composition before purchasing. Prefer Ecolabel certification, which certifies peat-free potting soil.

If you continue to use potting soils with peat, do so sparingly. Limit your use by reserving it for indoor plants and the most sensitive plants, grown in small pots with low water and mineral reserves, or those that cannot tolerate drought. For less fragile outdoor plants in large containers, you can create your own substrate composed of compost, garden soil, and coarse sand.

If you buy potting soil commercially, there is a very high probability that it contains peat. Indeed, it is almost systematically integrated into substrates for its physical qualities, in terms of lightness and water retention. However, the widespread use of peat has a significant environmental impact! This involves the destruction of wetlands that are ecologically […]

A friend of mine, who is also a well-known gardening columnist (and an excellent gardener, which makes for two significant differences between us), recently told me: “It annoys me, I can’t keep lavender alive…”

This was, I must say, a huge relief for me: I was not alone in carrying this shameful secret: repeatedly failing to keep one of the easiest plants in the garden, lavender.

This prompted me to make a public coming out and share with eager gardeners this specific know-how: how to fail at growing a lavender in 5 lessons!

Of course, not everyone is on equal footing: those who, like me, are fortunate enough to live in a cold, rainy climate with heavy soil will find it much easier to successfully fail at growing lavender than those unfortunate enough to live in the sunny climes of Provence.

However, by carefully following these simple and practical tips, accessible to all, I am sure many will also manage to kill their lavenders.

Lesson 1: to kill lavender, smother it!

Lavender comes from the South; it loves southern, stony, well-drained soils. It hates heavy soils that rot its roots in winter, which is why good gardeners prefer to plant in spring rather than autumn.

It can be planted in heavy soil, but requires drainage work: a large planting hole, at least twice the size of the pot, adding gravel or river sand, or, if necessary, turf.

So, to fail at growing your lavender, plant it at the wrong season (between November and February, for example) in heavy clay soil, which you have not lightened or loosened, ideally in a hole that is too small (if necessary, give a few frustrated heel kicks to make it fit);

This is a very reliable method for failing at lavender, which I have practiced extensively in our potato fields up North.

A rather perverse variant of this method is to put your lavenders in the position of gladiators in the circus games: plant lavenders very close together, say 15 cm apart: they will shade each other, and, by fighting, weaken one another, and part (at least) of your plants will end up dying, while the others will blacken, which is quite an effect.

Lesson 2: to fail at lavender, drown it!

Lavender does not appreciate repeated excess watering: it is a Mediterranean climate plant.

To kill lavender, water abundantly, not only after planting (which it likes, like all plants), but also throughout its (short) life: it will disappear by the first winter. To speed up the killing, create a watering basin that will keep the root ball moist during the dreary season, guaranteed success!

Lesson 3: to fail at lavender, put it in the shade

Lavender loves the sun… In the shade, it withers, stretches its branches sadly in search of light, flowers little or not at all, and dies quickly.

By planting in the shade (a true marked shade, it can flower quite well in light shade), you will achieve a result similar to the previous lesson. You can even combine lessons 1, 2, and 3 for a better result.

Lesson 4: to fail at lavender, overfeed it!

Used to poor soils, lavender behaves very poorly in rich environments: it eats too much, grows and grows… And very quickly collapses lamentably, leaving an awful black hole in the centre.

This lesser-known method is particularly recommended for sensitive souls; it allows you to fail at growing lavender (and many other things) in good conscience, through excess care: plant it in rich potting soil, generously amended with compost, supplemented by regular overdoses of fertiliser, preferably chemical: you may not kill it, but you will surely give it a rather monstrous appearance of a Chernobyl plant.

Generally, it is enough to plant poorly to fail. However, for safety, in case your lavender shows resilience, here is a maintenance tip:

Lesson 5: to fail at lavender, prune it regularly in a 'para' style

Like almost all evergreen plants, lavender does not like heavy or short pruning.

Of course, you can safely cut the dry flower spikes once a year (and make lovely fragrant bouquets), or a few overly exuberant young shoots. But do not prune the wood: it never regrows on old wood!

So to fail at lavender, prune it brutally and as short as possible: at the very least, you will make it look considerably ugly and prevent it from flowering properly; at worst, you will kill it. It is worth noting that even in Saint Rémy de Provence, this method works well.

Bonus tip for those who have had the courage to read everything, with a lazy method that I particularly recommend for its simplicity: you can also fail at growing lavender in a pot. Simply plant it in a small pot (say less than 20 cm), and do not water it. Admittedly, lavender does not like excess watering, but it is not a cactus: it needs water, which it seeks through a deep root system. For this reason, it does not settle well in a small pot (and above all, hates being moved).

You can therefore fail at it by simply keeping it in the tiny pot it came in when you bought it, while forgetting to water it!

Finally, to console the clumsy who, even by following these wise tips, still manage to keep a lovely fragrant lavender in the garden: even under good growing conditions, sun, well-drained soil, moderate watering, lavender does not age very well. It rarely lasts more than 10 years, especially in our Northern gardens, and generally becomes quite unattractive after 5 years: you will likely have the opportunity to see it die one day!

Discover everything you need to know about lavender to choose well, succeed in its cultivation, propagate it, or even dry it.

A friend of mine, who is also a well-known gardening columnist (and an excellent gardener, which makes for two significant differences between us), recently told me: “It annoys me, I can’t keep lavender alive…” This was, I must say, a huge relief for me: I was not alone in carrying this shameful secret: repeatedly failing […]

Once relatively unknown, Yuzu or "Yuzu Lemon" is currently experiencing a true surge in popularity. This is hardly surprising, as it is essential in Asian cuisine; this small Japanese lemon with its aromatic flavour is now used by top chefs and renowned pastry chefs alike.

And as is often the case with vegetables and fruits from Japan, buying fresh fruit is almost an impossible mission. But if you accept this challenge... and succeed, be prepared to pay the price: over 50 euros per kilo!

The best solution (after the black market or a friend who pilots for Japan Airlines) is, therefore, to plant your own Japanese lemon tree.

But before you dive in, let’s take stock of its uses, the taste of its fruit, its benefits, and how to cultivate it in our climates.

What is Yuzu?

The term Yuzu refers to both the fruit, the Yuzu lemons, and the small tree that bears them.

This Japanese lemon tree (Citrus junos, family Rutaceae) appears as a large bush with very thorny branches and evergreen foliage. It is believed to be the result of hybridization between the wild mandarin and Citrus ichangensis, or Ichang lemon.

From its parents, Yuzu has retained a remarkable vigour and hardiness, around -10 to -12 °C, which is uncommon for a citrus and allows it to be cultivated in our climates.

The Yuzu fruit, although often likened to a lemon, resembles more a large mandarin. About the size of a tennis ball, it is covered with a thick, slightly bumpy skin, which is green and turns yellow-orange at ripeness. Its flesh contains many seeds and produces relatively little juice.

Yuzu lemon fruits - Photos: Seahill, Edsel Little

Yuzu lemon fruits - Photos: Seahill, Edsel Little

What does Yuzu taste like? How to use it in cooking?

The flavour of Yuzu is unique and powerful. Very tangy, it can be described as a subtle blend of grapefruit, mandarin, and lime, with spicy notes of bergamot.

In cooking, Yuzu is suitable for both savoury and sweet preparations:

- the zest of Yuzu is used as a condiment to flavour fish and shellfish, as well as to enhance butter or add an original touch to a chocolate tart.

- the juice of Yuzu is used to marinate meats and fish, as well as to make exquisite sorbets. In pastry, it elevates fruity mousses and other creams, such as the delightful Yuzu curd.

Is Yuzu good for health?

Like all citrus fruits, Yuzu is known to be very rich in vitamin C. It is invigorating and may boost immunity. It is also believed to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.

By the way, did you know that a popular belief in Japan suggests taking Yuzu baths at the winter solstice to ward off colds for the entire year!

Look, it seems very fun!

Is it possible to grow Yuzu in your garden?

But before you can indulge in a Yuzu bath, you need to grow them… and, as I mentioned earlier, it is entirely possible in France.

Although hardy, Yuzu prefers warm and sheltered situations. Its cultivation in open ground is therefore mainly recommended in mild climates or in the area known as "the olive zone", which corresponds to the Mediterranean basin. Elsewhere, we advise you to install it in a large pot and move it to a cool place when a cold snap is forecast.

Vigorous but with a somewhat slow growth in the first few years, the Japanese lemon tree typically bears fruit after reaching the age of 4. The harvest occurs in autumn, from September to December.

This does require a bit of patience, but it will be rewarded with a harvest of delicious, rare, and original fruits!

Once relatively unknown, Yuzu or “Yuzu Lemon” is currently experiencing a true surge in popularity. This is hardly surprising, as it is essential in Asian cuisine; this small Japanese lemon with its aromatic flavour is now used by top chefs and renowned pastry chefs alike. And as is often the case with vegetables and fruits […]

We are approaching the end of the summer holidays, and many of us enjoy spending time by the Mediterranean... Holidays that are, of course, always too short! This frustrating phenomenon is something we strive to counter by giving our homes a touch of the Mediterranean! Whether it’s an antique pot, a small dry stone wall, an olive tree, a palm tree, a oleander, bougainvillea, an agave, and other "Mediterranean plants" whose mere mention brings us back to warmth and relaxation...

But what exactly is a "Mediterranean plant"? Is it a plant that grows spontaneously around the Mediterranean? A plant that thrives in a Mediterranean climate? A plant that has been produced in the Mediterranean basin? Let’s try to clarify...

The Mediterranean climate that we cherish is primarily characterised by warm, dry summers that are very sunny, alternating with mild, wet winters. It is a temperate climate, with well-defined seasons. Rainfall is infrequent and highly concentrated, particularly in autumn. In summer, precipitation is less than soil evaporation and the consumption of living beings, leading to a water deficit for which Mediterranean plants have had to develop avoidance strategies. Finally, let’s not forget the wind, with the mistral and tramontane rivaling the famous north wind we are more accustomed to at Promesse de Fleurs!

This type of climate leads to two other significant phenomena for the Mediterranean natural environment: a high pressure from human activities and numerous outbreaks of fire, as sadly highlighted by current events. Lastly, the poor, well-draining soils, whether acidic or calcareous, are always low in nitrogen and potassium, often supporting only low and sparse vegetation, particularly in the garrigues. But there is a silver lining! These strong constraints generate a diversity that is all the more significant, with the number of plant species in the Mediterranean reaching 22,500, of which just over half are endemic, meaning they are only found in that specific location on the globe. This provides a first element of answer to our question, "What is a Mediterranean plant?".

Among these species of Mediterranean plants, there are many annuals that bloom and die before or after the dry summer period, bulbs that take refuge underground, and a whole range of so-called "sclerophyllous" vegetation, meaning plants with tough enough leaves to prevent rapid water loss. In particular, there are evergreen oaks, cork oaks, kermes oaks, olive trees, of course, but also oleanders and conifers like pines and cypresses. Note that they compensate for their slowed activity in summer by the persistence of their foliage in winter, which makes them particularly appreciated in gardens. Others have the opposite strategy and lose their leaves to survive during drought.

We must also mention the special cases of aromatic plants, such as lavenders, thymes, rosemaries, sages, hyssops, myrtles... which release volatile compounds, the essential oils, limiting water loss. Some cistus, like Cistus ladanifer, use the same technique, in addition to having a very deep taproot system. The velvety leaves, even downright cottony, of Stachys or Ballotta, are also a very effective barrier against water loss, which has been exploited for a long time in drought-free gardens. Brooms, on the other hand, simply have no leaves... And of course, nothing prevents plants from combining protections!

However, we have not yet discussed palms, mimosas, or even prickly pears, agaves, bougainvilleas, oranges, pittosporum, and all the others that populate our holiday memories on the Côte d'Azur! These plants, which have perfectly acclimatised to the Mediterranean zone, to the point of sometimes becoming invasive, are not native to there: we must therefore look for their origins elsewhere.

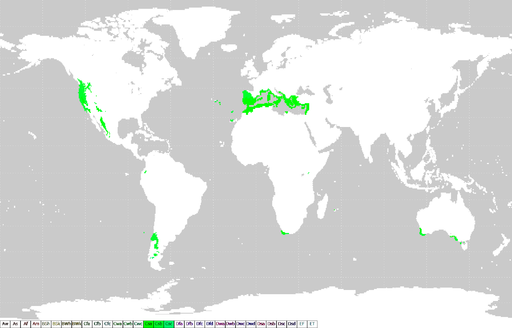

Indeed, while the Mediterranean region has given its name to its climate, it should not be inferred that the Mediterranean climate only exists around our beloved Mediterranean Sea! Similar conditions can be found in four other regions of the world:

- California

- central Chile

- South Africa

- southern Australia

Located on the western sides of continents, at latitudes between 30° and 45°, these temperate warm zones influenced by westerly winds correspond to the transition between subtropical and temperate climates in general.

From South Africa originate many Ericaceae and Proteaceae, well adapted to poor soils (the Proteaceae have a particular root system known as "proteoid" consisting of numerous short, closely spaced rootlets that are thought to improve nutrient solubility by altering the soil environment in which they grow). Highly sought after for cut flowers (Banksia, Protea) and for the production of flowering potted plants (the Cape heather, for example, which is found at All Saints), these plant genera are rarely encountered in our gardens, whether Mediterranean or not, due to their very delicate growing conditions.

In reality, outside of collections, we cultivate very few plants in Europe that originate from the "other" Mediterranean climates. Thus, we must look even further for the origins of "Mediterranean plants" in the sense of the collective and horticultural imagination, which is ultimately what matters when creating a garden.

The mimosa (Acacia dealbata) is native to the east of Australia, an oceanic climate zone, and was introduced in France in the mid-19th century. It has remarkably naturalised since on the Côte d'Azur, just like the Pittosporum tobira, which is also cultivated for its foliage, native to the subtropical climates of Japan and Korea. Other plants commonly found in Mediterranean gardens come from desert-type climates, such as agaves, yuccas, and cacti. With the exception of 2 species out of 2,500 (!), palms are not native to the Mediterranean but to tropical and subtropical climates, just like the citrus trees that thrive in the mild Mediterranean climate but must be irrigated in summer. The spectacular bougainvilleas originate from the humid tropical forests of South America!

Thus, it is important to highlight the contrast between the image of the Mediterranean nature, vibrant in spring, much more subdued in summer, which corresponds to a long period of near-dormancy for the plants, and the image one might have of the Mediterranean garden, which is much more lush but is mainly composed of exotic plants that require watering in summer! In practical terms, the term "Mediterranean plant" thus means both everything and nothing, as it mixes botanical and cultural aspects! Caution is therefore advised for the gardener...

Plants that grow in the Mediterranean in nature are quite hardy (often down to -10°C to -12°C) and adapt easily in gardens throughout the rest of France, provided the soil is very well drained, even calcareous, and that a fairly sheltered spot from frost is chosen for planting; they grow easily without irrigation, which is why they are increasingly being planted. Many are so familiar to us that we easily forget their Mediterranean origins, as is the case with aromatics. Conversely, plants that grow in the Mediterranean in gardens can equally be called "Mediterranean" as the former, but they are nonetheless exotic, more frost-sensitive, and should be reserved for pot cultivation in a conservatory or on the terrace in summer where they can be regularly watered and wintered in a sheltered spot.

We are approaching the end of the summer holidays, and many of us enjoy spending time by the Mediterranean… Holidays that are, of course, always too short! This frustrating phenomenon is something we strive to counter by giving our homes a touch of the Mediterranean! Whether it’s an antique pot, a small dry stone wall, […]