Plant bacterioses: how to treat and prevent them?

Everything you need to know about bacteria that attack plants and the damage they cause

Contents

Escherichia coli, Listeria, Salmonella… These bacteria are known for their danger to human health. But at the same time, other probiotic bacteria, present in large numbers in the intestinal microbiota, contribute to the proper functioning of our bodies. In short, for humans or animals, bacteria can be a double-edged sword: beneficial for some, formidable, even deadly, for others. Bacteria are also found in soil, in the air or in water that positively or negatively impact plants, bushes and trees… Some of these bacteria are phytopathogenous, causing serious bacteriosis. These bacterial diseases can cause substantial damage to foliage, flowering and fruiting, thus affecting the production of fruits or vegetables.

Let’s explore together the various bacterioses most detrimental to plants, as well as the best ways to combat them and above all to prevent the development and dispersal of these bacteria.

Plant bacteria: the good and the bad

Bacteria are, among living things, the simplest. They are found in nature in an almost incalculable number. Unicellular, a few thousandths of a millimetre long, these bacteria are visible only under a microscope. For example, it is estimated that more than a billion bacteria colonise a single gram of soil. An astronomical figure which can be explained by the dizzying rate of bacterial growth. Indeed, they multiply by simple cell division. Among these bacteria present in soil, air or water, some play a fundamental role for plants, while others are particularly detrimental, depending on the relationship they establish with them.

Leguminous plant roots with nodules on which Rhizobium bacteria attach

Indeed, some bacteria are completely neutral to the surface or tissues of the plants. There are saprophytic bacteria (feeding on dead organic matter), which include epiphytic or endophytic bacteria. Other bacteria establish a genuine symbiosis with the plants, in a give-and-take relationship. This is the case for Rhizobium-group bacteria, settled on the roots of leguminous plants, which fix atmospheric nitrogen and return it to the plants and the soil.

Other bacteria are very useful for maintaining soil fertility. Others are multiplied and deliberately introduced in biological control against pests. This is the case of the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), naturally present in the soil, which has been synthesised to act as an insecticidal agent against the larvae of certain Lepidoptera.

Finally, there are pathogenous bacteria that parasitize plants, causing qualitative and quantitative damage. There are about a hundred of these bacteria, harmful to plants, a number considerably lower than that of phytopathogenic fungi. They are responsible for bacterial diseases, called bacterioses, but their importance in plants is less than that of fungal diseases.

Further reading:

How do bacteria develop and spread in the garden?

These bacteria, good or bad, which can take the form of cocci, rods (bacilli) or spirillae (spirilla), live and persist in the soil, in crop or pruning debris, on seeds and seed stocks, on buds and foliage, on gardening tools, or even in the irrigation water from rainwater harvesting systems. In cases of extreme heat or cold (late frosts that affect plants), or by high humidity, resistant forms may appear and multiply, in the form of spores.

Next, dissemination occurs in several ways. Either wind does the job over quite a long distance, but inclement weather and insects such as the aphids or the mealybugs also enable the bacteria to travel. Just as the use of contaminated tools or human transport of infected plants.

Once they have reached their destination, the bacteria penetrate the plant tissues, via the stomata (the pores) of the leaves or the lenticels of the roots. More likely, it is through injuries, pruning wounds or the feeding punctures of piercing-sucking insects that the bacteria infest the plants. A plant weakened by multiple factors is naturally more vulnerable than a healthy, vigorous plant.

Leaves affected by fire blight

Once the bacteria have invaded the plant tissues, various symptoms appear: water-soaked (greasy) spots, necroses, cankers, galls or tumors, wilting, browning and/or leaf scorch, rots, gum oozing, and mosaic.

These symptoms can be common to those of cryptogamic diseases, which can sometimes make diagnosis difficult to establish.

What are the most common bacterioses in plants?

Following the bacteria involved, there are different types of bacterioses, more or less widespread depending on regions and climate conditions… As phytopathogenic bacteria are subdivided into different strains, the pathovars, they can attack multiple species.

- Fire blight (Erwinia amylovora) : it is the most dangerous bacteriosis for fruit trees, shrubs and plants in the Rosaceae family, pear trees are particularly susceptible. It can kill a tree in 8 to 15 months. This bacterial disease is subject to very strict legislation which requires, among other things, reporting any suspicious symptom to your local council. I invite you to consult Eva’s article to learn all about this disease: Fire blight: identify and control this disease

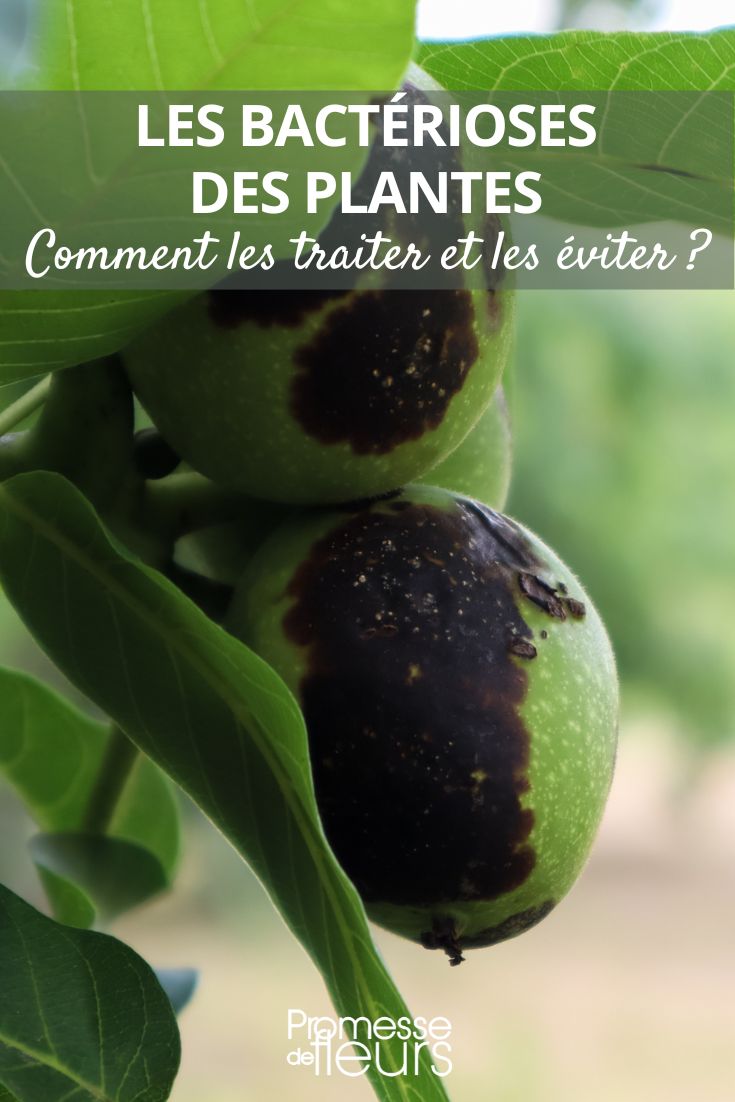

- Bacterial canker (Pseudomonas syringae) : this condition has become widespread in recent years, mainly on fruit trees (cherry, peach, plum, apricot, kiw i), but also on horse-chestnut trees. The bacterium, naturally present on leaves, develops in autumn and winter on the foliage, buds and May-blossom shoots, via leaf scars, cracks or injuries to the bark. In spring, symptoms appear: light-green to brown leaf spots, black spots on the fruits, depressed areas (necrosis) on the bark with gum exudation. In early summer, entire branches or the tree eventually die.

- Soft rot or bacterial rot (Pectobacterium carotovorum or Erwinia chrysanthemi) : the first bacterium attacks the roots, stems and fruits of cucurbits and solanaceous crops, lettuces, cabbages, celery… The second affects vegetable plants such as onions or potatoes, but also ornamental plants such as carnations, chrysanthemums or dahlias. In practice, the foliage wilts, browns then liquefies and decomposes. It can emit an unpleasant odour.

- Bacterial gummosis (Pseudomonas syringae or Xanthomonas spp.) which mainly affect beans and peas, but also cabbages, artichokes, tomatoes, cucurbits. These bacteria are transmitted by seeds and develop when a damp and windy period is followed by a hot, dry spell at flowering. One then sees angular, oily and translucent spots with yellow margins. The leaves brown and die, then the plant perishes within a few days. On peas and beans, dark green spots bordered with red appear on the pods.

- Bacteriosis caused by Xylella fastidiosa : this is a worrying bacterium arrived recently in Europe, which attacks a very large number of species. I invite you to read Olivier’s article: Xylella fastidiosa: a deadly bacterium for many plants!

Note that this list is not exhaustive!

Olivier infected with Xylella fastidiosa bacterium

How to combat these bacterioses?

Unfortunately, it is very difficult to combat these bacterial diseases, some, such as fire blight, being incurable. Few curative methods are sufficiently effective. However, for certain infections such as bacterial canker or grease, if detected early enough, it is possible to treat with Bordeaux mixture in 2 or 3 applications, three weeks apart, at the Bordeaux mixture. But with no certainty of success, and bearing in mind that the copper in Bordeaux mixture persists in the soil and pollutes the water.

Similarly, it is essential to remove and destroy the contaminated parts, often by digging quite deeply into the affected bark, before applying a wound-sealing compound. Burning them is the best way to eliminate them, but it is banned in gardens. Your remaining option is the recycling centre. The bacteria there will normally be destroyed by the heat at the heart of the compost.

The best way to combat these bacteria is to implement very strict prophylactic measures:

-

- Carefully remove all cultivation or pruning waste left on the ground

- Fertilise appropriately, and avoid manures that are too rich in nitrogen

- (appropriate watering, mulching) to avoid stress

- Prune with moderation and at the right time to thin the centre of the tree’s crown, and apply a wound-sealing compound to pruning wounds

- Try not to wet the foliage when watering, as excessive humidity is a vector for proliferation

- Respect a strict crop rotation

- Control vector organisms, such as scale insects and aphids

- Clean and disinfect gardening tools after each use

- Boost the plants’ immune defences with nettle manure.

The fight against bacterioses involves prophylactic measures

Finally, if your vegetable plot or orchard is frequently prone to bacterioses, ensure you select certified seeds or resistant varieties.

- Subscribe!

- Contents

Comments