We continue our journey through plants by introducing you to a species that spontaneously evokes Asia, yet can be found in a wide range of environments around the world. Indeed, it is often overlooked that this extraordinary giant grass also grows naturally in America, continental Africa, and Oceania.

A multi-purpose plant thriving in magnificent forests, with edible shoots, it is used to green gardens, as well as for building construction, furniture making, everyday objects, musical instruments, paper pulp, textiles, vinegar, and biochemical and pharmaceutical products... You may have guessed it, we are talking today about bamboo!

Bamboo

Bamboos are part of the grass family Poaceae and the subfamily Bambusoideae. Among the Poaceae, most grasses and cereals can be found. Plants in this botanical family are generally herbaceous - more rarely woody like the bamboos we are interested in here - possessing characteristics that distinguish them from other plant families. They notably have:

- cylindrical stems or culms with hollow internodes,

- alternate leaves,

- linear leaf blades with parallel venation,

- inflorescences in spikelets.

Bamboos are indeed grasses, and not trees or bushes, even though some can reach heights of 35 metres and diameters of 30 centimetres!

There are over 1600 known species, capable of growing in almost all climates and on the poorest soils. The main varieties include:

- Bambusa, originating from tropical and subtropical Asia, not very hardy, preferring warm and humid climates

- Chimonobambusa, elegant bamboos with moderate growth and lush foliage

- Fargesia, non-running and evergreen bamboos that are unlikely to escape the garden, well-suited for small spaces

- Phyllostachys, large bamboos that grow quickly

- Pleioblastus, dwarf or medium-sized bamboos, reaching heights of 10 cm to 3 m depending on species and varieties

- Sasa, distinguished by their small size and often compact habit.

The mysterious flowering of bamboos: this does not simply refer to what is usually written about it. When a bamboo flowers, all individuals of the same species flower worldwide... and die. While such a case can occur, it remains rare and is not the norm. Observing flowers on one species of bamboo does not mean that all will flower and perish: it is much more likely to be a sporadic flowering, affecting only a few individuals!

Bamboo groves are ubiquitous in the natural landscape of Asian countries, where they are found in the greatest numbers. But when and how did they travel to our gardens? Their journey is quite recent and due to a handful of enthusiasts.

The arrival of bamboos in the West

According to specialists, the first mention of a "bamboo grove" is found in a letter from Alexander the Great to his tutor Aristotle. This is not surprising, as this great conqueror of the 4th century BC had explorers study the Indus delta, among other things, to examine its flora and fauna. Pliny the Elder refers to bamboos in his Natural History written in the 1st century AD, and then in 1571, Mathias de l'Obel, a Flemish physician and botanist, also referenced a bamboo grove in his writings. In 1598, Willem Lodewijcksz, commissioner of a fleet sent to the Indian Ocean to the islands of Java and the Moluccas to purchase spices, reported: "We also saw grow in this manner the round Pepper, climbing and wrapping around tall and thick reeds, called in Portuguese Bambu, and in Malay Mambu. The Javanese etymology of the name bamboo is thus found. It designates a grass that has the shape of a hollow cane and is thought to be an onomatopoeia that could correspond to the sounds of a hollow tree in the fire.

In the 17th century, Georg Everhard Rumphius (or Rumpf), a Dutch merchant famous for his work in natural history, described over 24 species of bamboos. He referred to them in Latin as "Arundarbor" or "hollow trees" or "arborescent reeds". At the same time, Carl von Linné, the father of modern botany, catalogued around twenty bamboos. It is he who introduced the term "bamboo" into scientific vocabulary and classified them within the grass family. However, this did not bring bamboos to our regions...

Yet in the 18th century, great navigators brought back true botanical treasures by sea, ingeniously finding the water necessary for their irrigation. The nurseries of the time were already introducing multiple plants from abroad but these "curious tube-shaped trees" did not really attract interest in the West, whether for horticultural or agronomic exploitation.

The late arrival of bamboos in Europe is explained by Jean Houzeau de Lehaie, a Belgian botanist born in 1867, as "the rarity of fruiting, the short time that the seeds of many species retain their germinative capacity, and the slowness of transport. To cultivate bamboos in our latitudes, it was necessary to bring back plants rather than seeds. The sailing journey between the Far East and Europe could take up to six months, so botanists and nurserymen did not imagine bringing back bulky bamboo plants strong enough to withstand the journey and requiring very large water reserves. Technically possible, their journey was not worth the economic stakes, which were too low compared to other more ornamental plants.

It was the industrial revolution and the advent of steamships, shortening delivery times and facilitating the transport of goods, that finally allowed the introduction of bamboos in our latitudes. Thus, the Phyllostachys nigra was likely the first species to take root in the West in the early 19th century. Then, other bamboos were imported in 1840 by Alphonse Denis. The mayor of Hyères at the time, he acclimatised many plants from around the world in the garden of his property.

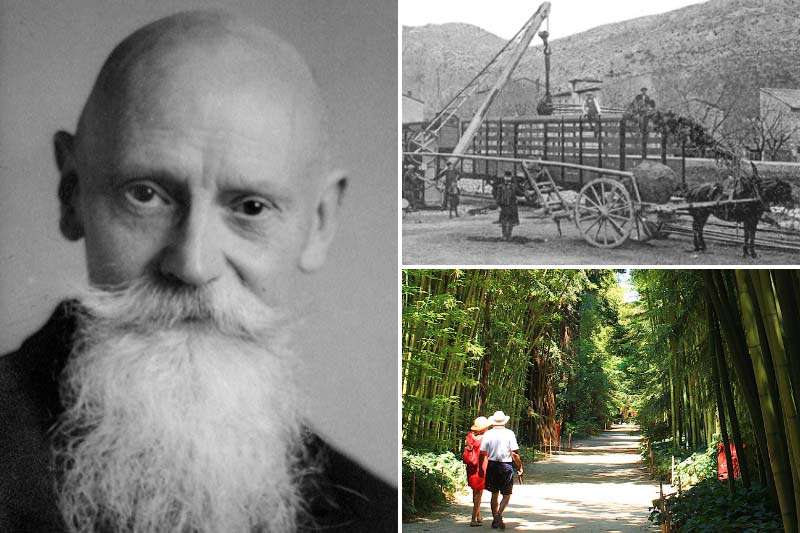

Jean Houzeau de Lehaie and the bamboo grove of Prafrance

Belgian naturalist Jean Houzeau de Lehaie (1867-1959) dedicated his entire life to the study of bamboos. He was only 16 when he began his first bamboo planting experiments on his family property. It is known that his initial attempts, starting with a small clump of Arundinaria japonica (Pseudosasa japonica) in open ground, were unsuccessful due to the rather cold and humid local climate. He was in contact with Louis Van Houtte, a Belgian horticulturist and botanist who was also responsible for the Royal Society of Horticulture of Belgium, who marketed Arundinaria falconeri as early as 1848 and Arundinaria fortunei (Pleioblastus fortunei) sent from Japan in 1863. As soon as they arrived, these plants quickly became part of Jean Houzeau's collection. He then initiated the introduction of new species from Japan, China, and India and their acclimatisation in Belgium at his property, L'Ermitage, near Mons.

Eugène Mazel is a passionate botanist from the Cévennes. Heir to a fortune, he began in 1855 to develop the Prafrance estate in Générargues, near Anduze in the Gard, and made his first bamboo plantings of Phyllostachys Mitis, Phyllostachys viridiglaucescens and Phyllostachys edulis alongside other exotic plants. The Bamboo Grove of Prafrance, which can be visited today and also includes a rich bamboo nursery, is one of the oldest bamboo parks in France. It is known that in 1887, many specimens were purchased by Jean Houzeau from Eugène Mazel, and from that date, almost every year his collection was enriched with several species or varieties obtained through exchange, purchase, or received from correspondents around the world.

For the development of communication routes in the regions of origin allows for an increase in the number of taxa, but also to have more resilient specimens. Until then, our enthusiasts had been content with plants collected near maritime ports, in areas with a regular climate. Now, a large part of the flora of China, Manchuria, Korea, or Japan was opening up to the world. And in the 19th century, silk importers brought back specimens to gift to their clients or plant in their properties.

Continuing to expand his collection and knowledge of bamboos, Jean Houzeau was also the editor of a periodic bulletin called The Bamboo, published between 1906 and 1908, and rich in a network of four hundred correspondents spread across the globe. Thanks to his scientific approach, he is the originator of the systematics of hardy bamboos. Throughout his life, he freely distributed numerous taxa of hardy and tropical bamboos in Europe, and then in Africa from an agronomic perspective: Phyllostachys violacens, aurea (in full bloom in 1922!), flexuosa or henonis (which flowered from 1904 to 1906) but also Fargesia nitida were thus distributed throughout Europe and planted in the parks and private or public gardens of the time.

Bamboo in our gardens

Grown in gardens around the world, in pots or in the ground, with their graphic foliage rustling at the slightest breeze and their robust culms, bamboos bring an undeniable exotic touch and structure the garden even in winter. They are classified according to their growth type: running species like Phyllostachys, which multiply rapidly through their rhizomes to the point of becoming invasive, and non-running bamboos known as "cespitose" like Fargesia that grow in compact clumps and are non-invasive.

Their height varies depending on the species, and they are classified into three size categories: the dwarfs measuring from 20 cm to 1.5 m in height, the small and medium ones from 1.5 m to 10 m, and the giants over 10 m. They allow for the rapid creation of evergreen hedges and, when associated with grasses, for example, they contribute to zen and graphic atmospheres, attractive throughout the seasons.

Wonderful plants for biodiversity

Bamboo is an integral part of Asian cultures, where its uses are multiple. But it is also an essential element of certain ecosystems: it serves as both habitat and food for the giant panda, the red panda, the mountain gorilla, the Vervet monkey of the Bale Mountains (an endemic monkey of Ethiopia) and the great bamboo lemur, all dependent on this plant.

Its rapid growth and strong root system make bamboo a powerful tool for soil protection and combating desertification worldwide. Estimates have shown that a single bamboo plant can bind up to 6 cubic metres of soil. Moreover, most bamboo species shed some of their persistent foliage throughout the year, thus improving soil health. Beyond its ornamental and culinary uses, bamboo is also a forage plant that can be used in phytoremediation.

There is an International Bamboo and Rattan Organisation (INBAR), an observer at the United Nations General Assembly, which promotes sustainable development based on the use of bamboo and rattan. Carbon storage, a resilient raw material that grows much faster than wood, allowing for the construction of affordable, strong, and flexible housing that is disaster-resistant, biomass fuel for cooking and heating... it is a plant with many advantages in the fight against climate change!

Further reading

- Discover all our varieties of bamboos

- To learn everything, browse our complete guide on bamboos: planting, pruning, maintaining

Comments