Botanical rules and nomenclatures

How to find your way around?

Contents

Botany offers an exciting universe of diversity and complexity, but for the novice, the rules and nomenclature can seem as impenetrable as a virgin forest. What is a cultivar or a nativar? How do you distinguish a variety from a subspecies? Why are names often written in Latin? If you have ever asked yourself these questions, this advice sheet is for you. We will demystify the principles of botanical nomenclature, guiding you step by step through its rules and conventions, so you can explore the world of plants with confidence and curiosity. Ready for the adventure? Then let’s dive into the fascinating language of plants.

Where does the standardised nomenclature in botany come from?

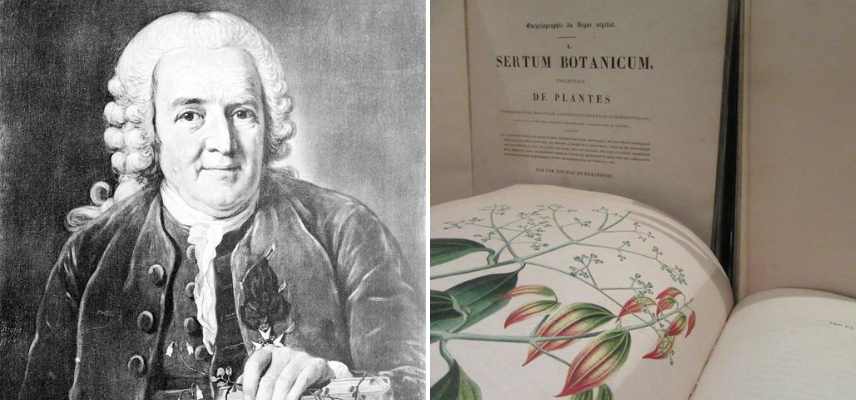

Botanical nomenclature has a long history, but most modern rules and conventions date back to the publication in 1753 of “Species Plantarum” by Carl Linnaeus (Carl von Linné), a Swedish naturalist. This work introduced the binomial system of nomenclature, which is now universally used in biology.

The binomial system gives each species a unique scientific name that consists of two parts: the genus name, which is shared with other related species, and the specific name or specific epithet, which is unique to each species. For example, for the human species, Homo sapiens, “Homo” is the genus and “sapiens” is the specific epithet. Names are generally based on Latin or Greek, although they may be derived from other languages.

Botanical nomenclature is governed by the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN). There are also similar codes for other groups of organisms, such as the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) for animals.

Codes evolve over time to account for new discoveries and scientific advancements. For example, with the advent of molecular biology, classifications based on genetic relationships have become increasingly important, sometimes leading to changes in nomenclature.

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), the inventor of the binomial system[/caption>

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), the inventor of the binomial system[/caption>

Read also

Men in the world of gardensAn official nomenclature: why is it so important?

This nomenclature is essential in botany (but also for the rest of biology) for several reasons:

- Communication: When scientists around the world use the same name to refer to a specific plant, it facilitates communication and the exchange of information. This is particularly important in scientific research, where results must be reproducible and accessible to an international audience.

- Precision: The binomial system of nomenclature allows for the precise and unique identification of each species. This avoids confusion that could arise from the use of common names, which often vary from region to region and can be applied to several different species. For sectors such as agriculture, horticulture, forestry, pharmacology, etc., precise species identification is essential. For example, knowing the correct species of plant can be crucial for food production, medicine, material production, and many other aspects of human society.

- Classification: Botanical nomenclature often reflects the evolutionary relationships between plants. Plants of the same genus are more closely related to each other than to plants of other genera. This organisation helps scientists understand the evolutionary history of plants and predict the characteristics of unstudied plants based on their classification.

- Conservation: Botanical nomenclature also aids in the conservation of species. By having a universally recognised system for identifying plants, efforts to protect endangered species can be better coordinated across international borders.

Please note: for now, in botany, there are no standardised names in French, unlike in ornithology, for example. Plant names in French can thus be vernacular or common (usual names in a certain language, national or local, or even a dialect) or vulgar (translation into everyday language of the Latin name or a vernacular name). Although often confusing, these names are still widely used and hold considerable importance in ethnolinguistic heritage. After all, we ourselves refer to a daisy flower (“which blooms at Easter”) and not to the inflorescence of a Bellis perennis.

A Latin name to be understood worldwide

A Latin name to be understood worldwide

How to name plants?

The naming of plants follows the binomial nomenclature system, which was standardised by Carl Linnaeus in the 18th century. Each plant has a unique scientific name in two parts:

- The genus name: This is the first part of the name and is always written with a capital letter. For example, in the case of “Rosa chinensis“, “Rosa” is the genus name and is shared by all roses.

- The specific epithet: This is the second part of the name and is always written in lowercase. In the example “Rosa chinensis“, “chinensis” is the specific epithet, indicating that this species of rose is native to China.

Together, these two terms form the scientific name of the species, which is often written in italics to distinguish it from the surrounding text. Sometimes, a third name is added to designate a subspecies, variety, or form.

It is important to note that these names are often based on Latin or Greek, but they can also refer to people, places, characteristics of the plant, or almost anything that the discoverer of the plant wishes to commemorate.

The authority of the name

In botanical nomenclature, the name of the botanist (or a group of botanists) who first described a plant is often added after the scientific name of the plant, in abbreviation (less commonly the full name). This is known as the authority of the name. For example, in the name “Quercus robur L.”, “L.” is the abbreviation for “Linnaeus”, the botanist who first described this species.

It is important to note that, according to the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN), the authority of the name is not an official part of the scientific name of the plant, but it is often included to provide additional information. When the name of a species is modified (for example, if a species is moved to a new genus), the authority of the name may also be changed to indicate the person who made the change.

Variety, subspecies, cultivar...: how to make sense of it all?

Subspecies

A subspecies is a taxonomic rank in botany, situated between species and variety. Higher than variety, a subspecies is used to designate groups of plants within a species that have distinct characteristics and a particular geographical distribution, but are capable of interbreeding.

These subgroups generally have specific adaptations to certain environmental conditions or are geographically isolated from other groups within the species, leading to distinct differences in their morphology or behaviour.

The name of the subspecies is always written in lowercase and is preceded by the term “subsp.” (or “ssp.” in abbreviation) placed between the species name and the subspecies name. For example, in “Helichrysum italicum subsp. microphyllum” (Italian Everlasting or Curry Plant), “Helichrysum italicum” is the species name, and “microphyllum” is the subspecies name.

It is worth noting that the boundaries between variety, subspecies, and species can be blurred and are often subject to debate among botanists and biologists. Classifications can change over time with advancements in scientific understanding.

Variety

In botany, a “variety” is a taxonomic rank below species. It is used to designate populations of plants within a species that exhibit minor but consistent differences from the species norm. These differences may relate to colour, shape, size, or other morphological characteristics. These populations are generally naturally occurring and are capable of interbreeding with other varieties within the same species.

The name of the variety is always written in lowercase and is preceded by the term “var.” placed between the species name and the variety name. For example, taking cabbage, it is a variety of Brassica oleracea (common cabbage) and should be written as: Brassica oleracea var. capitata.

It is important to note that the term “variety” in botany has a specific technical meaning and should not be confused with the common usage of the term in horticulture or agriculture, where it is often used interchangeably with “cultivar” to refer to variants of a plant that are clonally propagated to maintain specific characteristics.

Cultivar

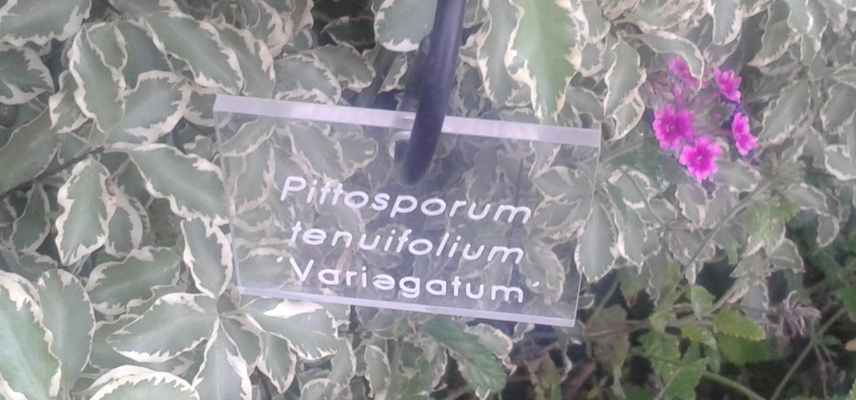

A “cultivar” is a term used in botany and horticulture to refer to a plant selected for desirable characteristics that are maintained during propagation. The term “cultivar” is a contraction of “cultivated variety”.

A cultivar may be selected for many reasons, including a particular size, flower colour, resistance to certain diseases, tolerance to specific environmental conditions, or high yield. Once a plant is selected as a cultivar, it is generally propagated clonally (by propagation by cuttings, grafting, division, etc.) rather than by seeds, to ensure that the descendant plants retain the desirable characteristics of the parent.

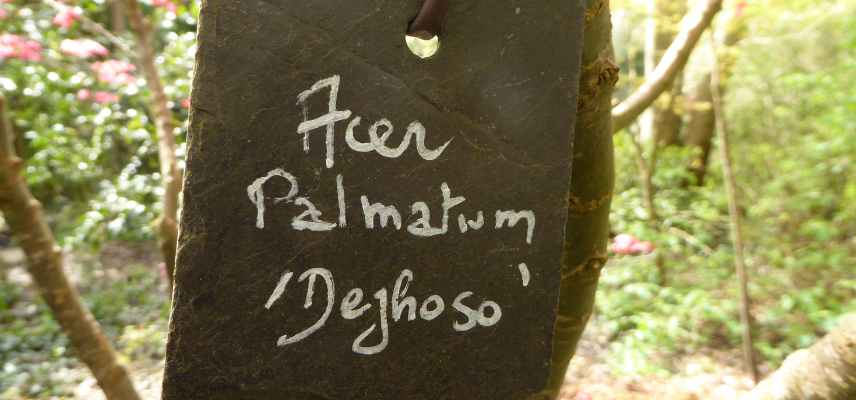

In terms of nomenclature, the name of a cultivar is generally written in lowercase, enclosed in single quotation marks, and placed after the scientific name of the species. For example, Acer palmatum ‘Atropurpureum’ is a cultivar of Japanese maple with red leaves.

It is important to note that cultivars are often the result of human horticultural and agricultural efforts, whereas taxonomic ranks such as species, subspecies, and varieties are generally used for groups of plants that have naturally differentiated in the wild.

Did you know?: A “nativar” is a relatively recent term in the field of horticulture. It is used to describe a cultivar derived from a native or indigenous plant. These plants are often chosen and propagated because they possess desirable characteristics, such as beautiful flowering, colourful foliage, or resistance to certain diseases, while also retaining many traits of their wild native parents: for example, the Quercus robur ‘Fastigiata’. In terms of nomenclature, nativars are generally designated in the same way as other cultivars, with the cultivar name in lowercase, enclosed in single quotation marks, and placed after the scientific name of the species. However, please note that the use of the term “nativar” is less standardised and accepted than terms like “species” or “cultivar”, and it may not be recognised or used in the same way by all botanists or gardeners.

The Special Case of Hybrids

In botany, a hybrid is the result of crossing two plants of different species or genera. The naming of hybrids follows certain rules and conventions depending on the type of hybrid.

- Interspecific Hybrids: These hybrids are the result of crossing two different species within the same genus. The name of the hybrid is generally formed by combining the genus name with a specific hybrid epithet, often “x hybrida”. For example, Petunia × hybrida is a hybrid of different species of Petunia. Sometimes, the names of the two parent species are combined to form the specific epithet.

- Intergeneric Hybrids: These hybrids are the result of crossing two plants of different genera. The name of the hybrid is a blend of the names of the two parental genera. For example, the Fatshedera (x) lizei is a hybrid between a Fatsia and a Hedera (ivy).

-

Cultivated Hybrids: These hybrids are often created in horticulture. They can be named like other cultivars, with a cultivar name placed after the scientific name of the species or hybrid, usually in single quotation marks. For example, Rosa × hybrida ‘Peace’ (synonymous with ‘Madame A. Meilland’ and ‘Gloria Dei’), a hybrid tea rose, is a specific cultivar of a rose hybrid.

To lose one's way...

The ending of the specific epithet (the second term in the binomial name) in botany is generally determined by the grammatical gender of the genus name (the first term), in accordance with the rules of Latin grammar.

In Latin, there are three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. Each has different endings for adjectives, which are often used as specific epithets. For example, a feminine genus name like “Rosa” (rose) could have a specific epithet “gallica” (of France), forming “Rosa gallica” (the French rose). The same applies to Geum coccinum, Leymus arenarius, or Cercis canadensis.

But…

However, it is important to note that not all species names strictly follow this rule (for example: Stachys byzantina or Cornus sanguinea). Many specific epithets are proper names, place names, or words derived from Greek, which may not conform to the declension rules of Latin. For instance, in “Quercus robur” (the pedunculate oak), “robur” does not change, regardless of the gender of “Quercus”.

Furthermore, some specific epithets are non-Latin forms or poorly Latinised, either by historical tradition or because they were introduced after Latin nomenclature was standardised.

Indeed, but also…

In botany, an ending in “ii” or “iae” in a species name is generally an indication that the species has been named in honour of a person. This naming convention is often used to honour the discoverer of the species, a famous botanist, or sometimes another notable individual.

When the species name ends in “ii” or “i”, it generally means that the species has been named in honour of a man. For example, the species “Abies magnifica var. shastensis” was renamed more simply to “Abies shastensis” in honour of D. E. Shasta.

When the species name ends in “iae”, it generally means that the species has been named in honour of a woman or a family. For example, “Rosa banksiae” is a species of rose named in honour of Lady Banks, the wife of botanist Sir Joseph Banks.

All these species names are said to be “invariable” and retain their original form, regardless of the ending of the genus name.

Rosa banksiae and Viburnum plicatum Mariesii

- Subscribe!

- Contents

Comments