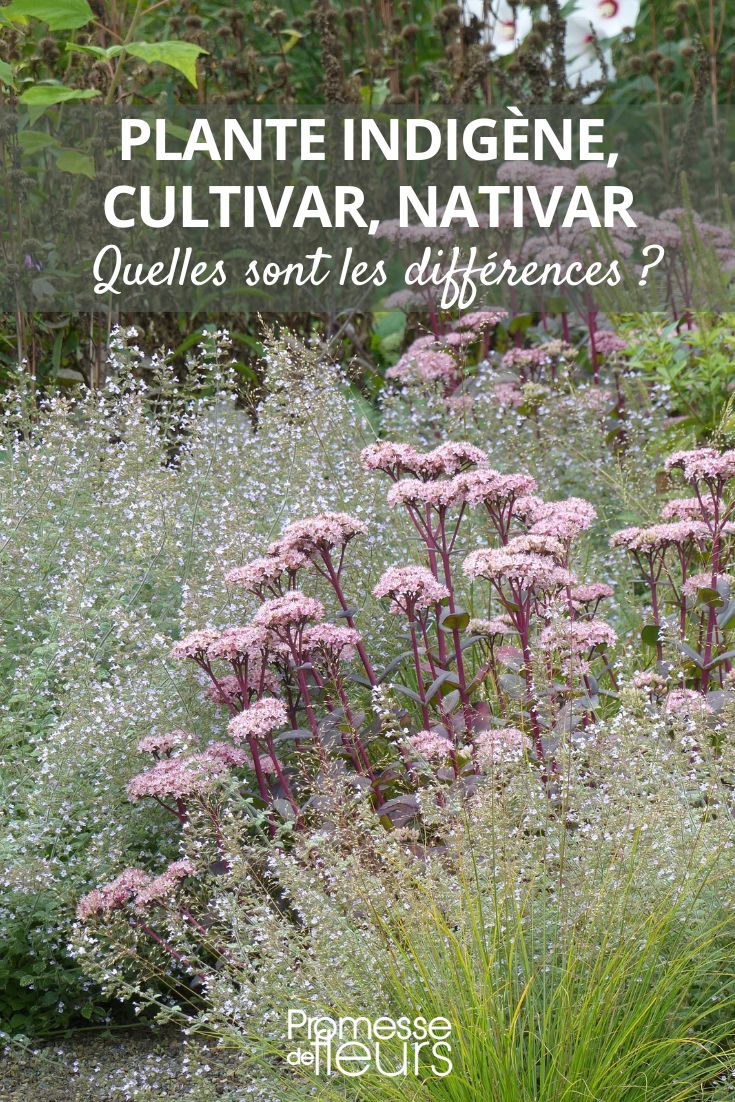

Native plant, cultivar, nativar: what are the differences?

How to navigate botanical vocabulary? Native species and horticultural varieties under the magnifying glass.

Contents

Helleborus foetidus and Helleborus x iburgensis ‘Barolo’. Two hellebores that, at first glance, differ by the colour of their flowering, one offering pale-green flowers edged with purple, the other wine-red. Yet behind these two “simple” names lie further differences that even somewhat seasoned gardeners can discern through typography. Indeed, behind these two hellebores lie two different species, one native and one horticultural variety, also known as a cultivar, arising from hybridisation…”“Native”, “cultivar”, “hybridisation”…” Have I lost you with these purely botanical terms? Knowing that I could add to the list the anglicism “nativar”, which is starting to emerge…

So let’s take stock of these different species and varieties that grace our gardens to learn how to distinguish a native plant, a cultivar and a nativar. And above all, let’s try to understand their role in the sustainability of our ecosystems and the maintenance of biodiversity.

Further reading :

- COP 15 on biodiversity: a hope to save nature?

- April 22 is Earth Day

What exactly is a native plant, and what are the benefits of planting one?

A native plant is a plant species that naturally grows in a region or an ecosystem without any human intervention. Its presence in a given place is the result of an evolutionary process spanning millennia, which makes it particularly well-suited to the environment in which it grows.

A plant in the wild

Thus, a native plant is a plant that has not been modified. It has remained in its natural state and occurs in the wild in a given medium and climatic zone. Native plants therefore grow spontaneously along roadsides or river banks, on embankments, in hedges… or reclaim their place in abandoned gardens, according to their cultivation requirements. They reproduce by self-seeding or have naturalised in a defined space, without human intervention.

Obviously, a native plant in southern France will not be native in the north. Indeed, native plants are defined in relation to biogeographical regions with their ecological, geological and climatic characteristics…

The benefits of planting native species

Often referred to as “wild plants” or “native plants”, native plants are today on the rise. It must be said that they have a crucial role in the preservation of biodiversity and bring numerous benefits to local ecosystems. Planting native species in your garden is therefore a big step for environmental preservation. Especially with climate change advancing. But why, you may ask?

- Native plants form the basis of the local food chain and provide food and shelter to various animal species, notably pollinating insects, birds, some small mammals, a few reptiles or amphibians… This interaction between plants and animals promotes pollination, seed dispersal and the survival of many species.

- Native plants show a certain resilience to local diseases and parasites. This helps reduce the use of harmful products for the environment.

- Due to their natural adaptation to their environment, native plants require little or no maintenance, watering or fertilisation, therefore less work. They are moreover hardier and more resistant to climatic conditions such as drought.

Hawthorn (Crataegnus) is a native plant widespread in our rural landscapes and beneficial to local wildlife

Native plants are therefore key elements of local ecosystems. They help to maintain ecological balance and to preserve the richness and diversity of ecosystems.

To learn more and discover a few native species :

- Plant native species to attract pollinating insects

- Native plants: let’s take stock!

But, in brief, among native plants, the poppy (Papaver rhoeas), gorse (Cytisus scoparius), purple foxglove (Digitalis purpurea), hawthorn (Crataegnus), elder (Sambucus)… and our stinking hellebore that grows naturally at woodland edges or in clearings.

Read also

Botanical rules and nomenclaturesUnderstanding what a cultivar is and its characteristics

A short etymology lesson to begin: The word “cultivar” is derived from the contraction of “cultivated” and “variety”, meaning that a cultivar is a plant selected and cultivated by people in relation to certain of its characteristics. These cultivars may arise from cross-breeding, selections, hybridization, natural mutations… carried out for a specific purpose. Therefore, a cultivar has been created and obtained artificially and intentionally, thanks to human intervention at some point. It is then grown for specific characteristics such as the colour of the flowers or the foliage, the fragrance of flowering, the shape of the leaves, the size of the plant, its rate of growth, hardiness, its adaptation to climatic conditions… for an ornamental plant. As for vegetable plants, they are also selected and hybridised for their productivity or profitability, their resistance to diseases, the flavour of their fruits or vegetables… A cultivar is therefore an horticultural variety that contrasts with botanical varieties.

Agapanthus africanus and two of its cultivars, Agapanthus ‘Back in Back’ and ‘Album’

Today, the main ornamental garden plants such as the roses, the camellias, the rhododendrons, the hydrangeas… but also perennial plants, bulbs, shrubs… are cultivars obtained through rigorous selections. And their multiplication is mainly by propagation by cuttings or division. Indeed, most cultivars do not reproduce by seeds, as sowing does not preserve the characteristics.

How to recognise a cultivar? To understand, let’s take the example of the Japanese spiraea (Japanese spiraea (Spirea japonica) ‘Little Princess’), a charming small shrub with soft pink flowering. It is a cultivar derived from Spirea japonica, developed by people for its abundant flowering, but certainly also for its modest size and its spreading, dense habit. Here, Spirea japonica, always written in italics and in Latin (or Latinised Greek) designates the genus (Spirea with a capital) and the species (japonica without a capital). As for ‘Little Princess’, it is the variety (that is, a cultivar) always designated with a French, English or Japanese term, written in roman type, with capitals and enclosed in single quotation marks.

How does the nativar fit between a native plant and a cultivar?

The nativar is an anglicism, arising from the contraction of “native” and “cultivar”. In other words, a nativar is a horticultural selection of a native plant. It may be the result of a natural genetic variation discovered in the wild, or of an artificial selection based on horticultural traits. Nativars thus preserve the qualities and characteristics of native plants, while some aspects are improved. Thus, a nativar will offer nectar-rich flowers compared with the native plant, its growth will be faster, or its resistance to disease higher. They offer aesthetic advantages, improved resilience and growth compared with their wild counterparts, while retaining adaptability and resilience.

From a botanical perspective, nativars are not purely native plants since they do not grow naturally in this form. Nevertheless, they are not cultivars, as they have not been fully introduced.

Heather Calluna vulgaris ‘Bonita’ can be regarded as a nativar of the heather found in our countryside and heathland

These nativars are generally perfectly suited to the local ecosystem and can promote biodiversity by attracting native pollinators such as bees or butterflies.

To help you understand, take the example of the field maple (Acer campestre). It is a tree native to Western Europe and therefore native and very common in our countryside. It is also an interesting tree for its ornamental qualities, but also its melliferous properties. It is therefore a tree that promotes biodiversity. Today you can find the Acer campestre ‘Carnival’, a small field maple with white and pink variegated foliage. It is literally a nativar that has retained the robustness and hardiness of its native parent, while displaying specific leaf characteristics.

Native plant, cultivar, nativar... how to distinguish them and which to plant?

Now that you can clearly tell native plants apart from cultivars and nativars, it is important to know how to distinguish them at purchase. Olivier provides a few pointers in his article titled Botanical rules and nomenclatures, how to navigate them?

To keep it simple, a cultivar or a nativar is designated by single quotation marks that accompany the genus and species in italics.

However, nothing really distinguishes native plants, whether on our site or at a nursery. The French Biodiversity Office, a public establishment dedicated to preserving biodiversity, has, however, created the ‘Local Plant’ label that lists 704 native plants, available in 23 biogeographical regions. Otherwise, you can wander the countryside around you with a keen eye, and, above all, a good plant-identification app on your mobile to identify what grows there naturally. You can also let nature take its course, and in particular the wind, birds, ants… which could disseminate a few seeds into your garden.

And in your garden, which plants should you favour? Native plants, cultivars or nativars? Simply all three. Indeed, all these plants have a positive impact on the planet, the climate and the soils… They sequester carbon, they stabilise soils and prevent erosion with their root system, they facilitate water infiltration and reduce runoff, especially in regions affected by drought and floods. Finally, all reduce pressure on endangered species by providing shelter and food for wildlife. All help to maintain ecological balance.

Admittedly, planting cultivars often responds to aesthetic considerations or a need (to hide from neighbours, to shield from wind, to camouflage a damaged façade, to cover a mound…) but they also play their part in biodiversity, even if their nectar is less abundant, their vegetation less dense, their berries less appetising… Cultivars thus offer a wide aesthetic variety (ideal to combat boredom and sameness) and adaptation to specific conditions, among other climatic factors.

As for nativars, they may be better suited to the local ecosystem than cultivars. But nonetheless, some may also diverge significantly from their native ancestors.

So, in the garden as elsewhere, long live biodiversity! The essential aim is mainly to multiply flowering, woody and herbaceous species to offer varied food for insects and their larvae, but also nesting sites for birds, refuges for small mammals. And to please you with double flowering (where insects cannot access them), variegated or coloured foliage, exotic shrubs… less useful to local wildlife, but good for your mood.

- Subscribe!

- Contents

Comments