Oak gall: what is it?

Why does it occur, how to identify it, and what dangers does it pose to the tree?

Contents

They can come in various shapes and colours: the galls of the oak are growths secreted by the tree itself in response to the sting of a parasitic insect. These swellings or deformities can sometimes be quite impressive and may resemble a disease. But what is the reality?

Let’s see how to recognise the different galls of the oak, what their impact is on the health of the tree, and whether it is possible to prevent them.

His Majesty the Oak

The formation of a gall

Consequences of a Bite from a Parasitic Insect

When specific parasites bite oak trees, they develop a natural reaction known as “gall” or “cecidium.” These are actually growths of various types that can develop on several parts of the plants.

The small parasites responsible for the bites causing these deformities are primarily insects or mites (arthropods). In oaks, it is mainly insects from the family Cynipidae, resembling small hymenopterans, that are responsible for the galls: flies, wasps, aphids, etc. In rarer cases, they may involve fungi, viruses, bacteria, or nematodes. These parasites are also referred to as “gall-makers” or “gall-inducers,” meaning they live and cause the appearance of galls. When they bite, they lay eggs that will develop into larvae. These larvae are then perfectly protected and naturally nourished by the plant’s tissues within the growths or swellings generated. Galls thus serve as a true cocoon.

Therefore, it is not a disease, but in response to the presence of these parasites, the oak naturally develops benign “tumours” at the site of the bite. The comparison is often made to the appearance of bumps on the human body following an insect bite. When biting, the parasites also inject a kind of chemical substance responsible for the deformation of the tissues.

Galls can appear on leaves, stems, terminal buds, flowers, acorns of the oak, or even on the roots. Several different galls can coexist on the same tree. They initially resemble small pustules that will grow over time. This reaction of the tree helps to isolate the larvae. The swellings continue to be supplied with sap by the oak and may remain in place even after the larvae have emerged.

The “gall” should not be confused with the “scabies,” a contagious skin disease caused by a parasite that can affect humans or animals.

It is worth noting that galls exist on many other plants: roses, dog roses, lindens, spruces, beeches, etc.

For more information, feel free to refer to Olivier’s article: “Plant Galls: What Are They?.”

Life Cycle

It depends on the implicated parasite. There can be two cycles per year, developing on different parts of the oak, depending on the seasons.

For the small wasp Neuroterus quercusbaccarum, for example, it is often in spring that the eggs are first laid, leading to the initial galls on the buds. The larvae will then develop until maturity before leaving their cosy nest during the summer. This generation, consisting only of females, will lay eggs a second time during the summer, this time primarily on the oak’s leaves. It is agamous, meaning reproduction occurs through parthenogenesis, without mating with males.

By autumn, when the leaves fall, the larva of the second generation will find itself on the ground, protected in its cocoon where it will spend the winter. Once adults in the following spring, males or females will emerge, and the cycle will begin again.

Overall, galls on oaks can be found from spring to autumn.

The scientific study of galls encompasses both botanical and entomological knowledge (the study of insects): this field is known as cecidology.

Read also

Oaks: planting, pruning and careThe different forms of oak galls

There is a wide variety of galls, which differ again depending on the concerned parasite, but also the laying area. Sizes, colours, textures, shapes… are all characteristics that help to differentiate them. Here are some of the most common oak galls.

The lenticular gall

It is located on the underside of the leaves and develops in the presence of Neuroterus.

- The laying of the wasp Neuroterus numismalis generates small circles of 2 to 3 mm, with a hollow centre and thick edges, revealing small golden-brown hairs at their core. They almost resemble mini cereals.

- The laying of Neuroterus albipes induces hairy or smooth circles, with a small bump in the centre and edges that can be undulated. The colour of these galls varies from white to red.

- Neuroterus quercusbaccarum is responsible for brown-red galls made up of hairs. They measure between 3 and 5 mm. In August, these galls detach before the foliage falls to continue their cycle on the ground.

Manifestations of Neuroterus numismalis, Neuroterus albipes, Neuroterus quercusbaccarum (© Sally Jennings)

The cherry gall

This is a larger gall, reaching 10 to 30 mm. It follows the sting of the small fly Cynips quercusfolii. Logically, as its name suggests, it has a round cherry-like shape, with a pale green colour veined with red, sometimes appearing spongy. It is found on the underside of the leaves, which fall to the ground in autumn.

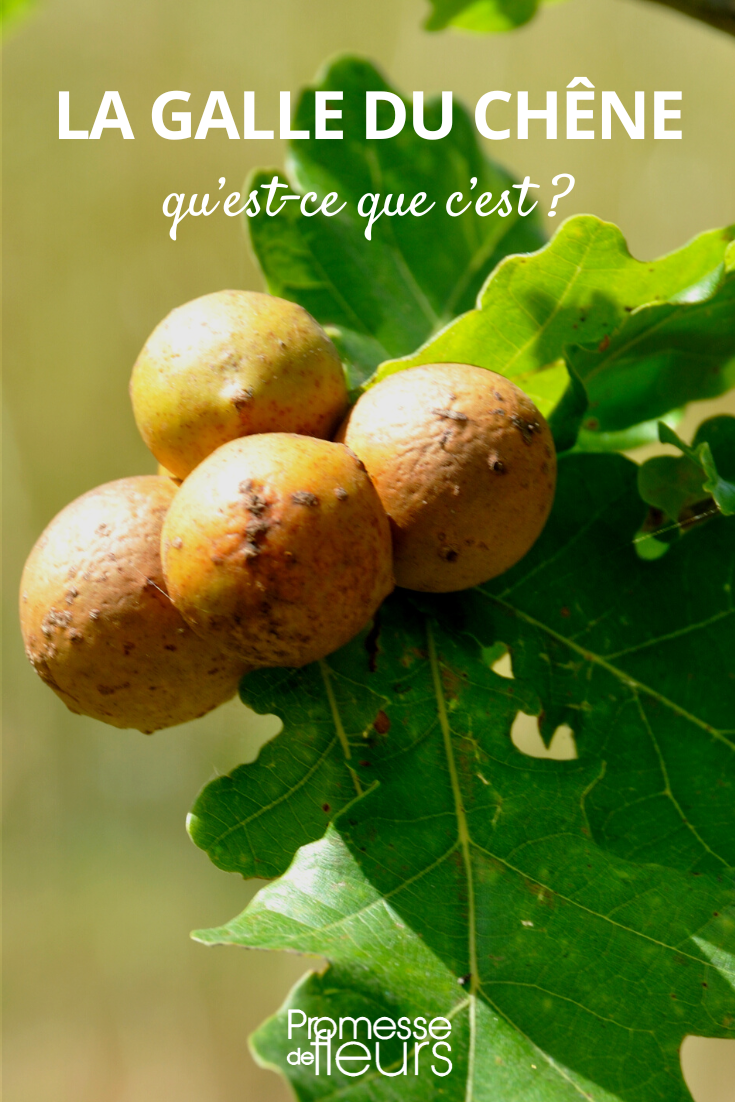

The round gall or walnut gall

This gall is generated in the presence of the round gall wasp (Andricus kollari). It measures between 12 and 25 mm in diameter and forms an almost perfect circle. It is found on the terminal buds of the pedunculate oak. Initially green, it turns brown over time. Its texture can be smooth or rough.

The oak apple

This gall resembles a spongy red apple, found on the terminal buds of the tree. It then dries and turns brown. Once fully dry, it can resemble a sort of mini fossilised beehive, with its small larval chambers resembling alveoli. It is caused by the insect Biorhiza pallida.

Manifestations of Cynips quercusfolii, Andricus kollari, Biorhiza pallida (© Sally Jennings)

The largest oak gall

It is the result of stings from the insect Andricus quercustozae and is one of the most impressive. In terms of diameter, it reaches between 30 and 35 mm. It resembles the cumbersome ball found at the end of a medieval weapon (the mace), with its crown of small spikes. This large sphere is brown and develops on the buds.

The artichoke gall

It resembles a scaly cone, reminiscent of the famous vegetable. It is the small wasp Andricus foecundatrix that is responsible for it. This gall appears on young buds, particularly on the sessile oak.

The acorn gall

This gall appears on the cupule, the small cup that partially surrounds the fruit. It resembles a sort of strange mushroom, which can eventually completely cover the acorn. Initially green, these galls later turn brown to red and have a hard, woody texture. They eventually fall in autumn. It is the small wasp Andricus dentimitratus that induces the development of this gall, which is said to be more common in Mediterranean regions.

To learn more about these natural deformations, which can sometimes be very aesthetic, discover this additional article on a collection of oak galls.

Manifestations of Andricus quercustozae, Andricus foecundatrix, Andricus dentimitratus (© Ferran Turmo Gort and naturgucker.de)

Discover other Oak

View all →Available in 1 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

Available in 4 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

Available in 2 sizes

Available in 2 sizes

What dangers does the oak face when developing a gall?

So, are these galls harmful to our trees? They are generally benign, especially if they appear on healthy, mature specimens.

However, in excessive quantities, they can sometimes weaken the tree by:

- delaying growth or impacting the development of a stem or fruit;

- limiting photosynthesis when they are on the leaves;

- reducing nutrient absorption when they are on the roots.

Let’s remember that oak galls are not diseases. They allow the tree to isolate their parasite, thus limiting its impact on the plant’s health. Their damage is mostly aesthetic, although these curious deformities can sometimes reveal a decorative character.

There is not really a preventive measure or treatment to stop oak galls from developing. Their appearance varies from year to year. We therefore advise you to let nature take its course while admiring its creativity!

And if you still wish to take action, you can remove the affected leaves or cut the branches and buds using a pruning shear. Note that it is unnecessary to use insecticides to eliminate the parasites present in the galls: the protective shells formed by the oak keep them well shielded from this type of attack.

Read also

Plant galls: what are they?Use of Oak Galls

The largest oak galls are sometimes dried and used as original decorations: this is an easily collected, free, and natural resource.

Galls are concentrated in gallic acid, an organic and aromatic substance. It is thanks to these tannic acids that galls can be used to create ink, dyes for tanning leather, or even fabric dyes. They are believed to have been used for these purposes since the Middle Ages. Today, some use them to make plant-based inks or to colour fabrics.

- Subscribe!

- Contents

Comments