The different types of root systems

Let's see what's happening underground...

Contents

What defines a good plant is not paradoxically its upper part (stems, flowers, leaves…) but rather its root system. This must be strong and healthy for the plant to anchor itself securely and also to feed properly. It is the hairs attached to the roots that will absorb water and nutrients. However, the roots also serve as reserves for the plant: this is well known for rhizomes and tubercles, but it is also true for other types of roots, particularly for perennials and deciduous woody plants, whose sap descends in autumn into the root system to store enough nutrients to restart growth in spring. It is also worth noting that the roots provide an interface with various living organisms in the soil, known as the rhizosphere effect. However, while the roots always have the same roles, not all plants have the same root system. These root systems can differ depending on the species of the plant, as well as the nature of the soil or the availability of water and nutrients. Let’s take a look at these different root systems!

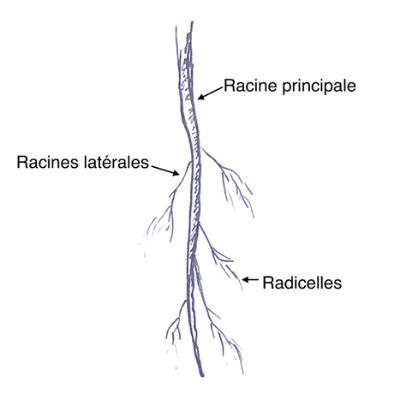

The tap root system or tap root

Basically, it’s a carrot! This type of root system can be found in many plants, particularly among dicotyledons and gymnosperms (conifers, Cycas, and Ginkgos).

The main root burrows deeply and vertically into the soil, while lateral secondary roots develop from it. Taproots can take on several shapes: conical like a carrot, fusiform like a long radish, or napiform like a turnip. Plants with this type of root system are difficult to uproot and transplant. Many taproots have evolved to become particularly efficient storage organs.

A few examples: Tomato, carrot, parsnip, radish (yes, what we eat is just a swollen taproot!), oak, hawthorn, pine, spruce, dandelion…

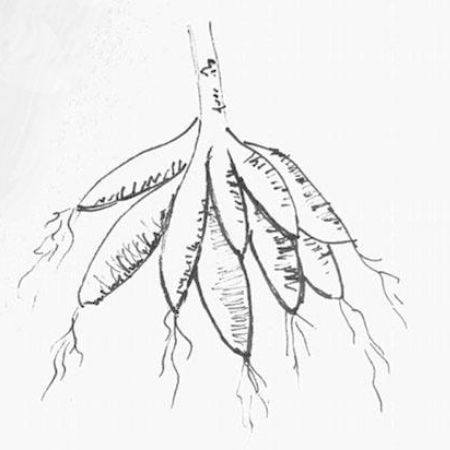

Taproot © Gwenaëlle David-Authier

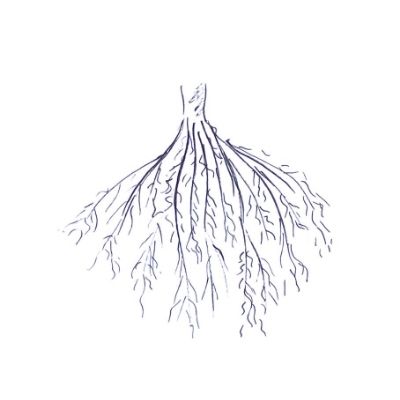

The fasciculate root system

A root system more commonly found in monocotyledons, particularly grasses and bulbous plants.

The fasciculate root system forms a bundle of roots that all originate from the same point, meaning there is no main root. This is clearly visible when pulling up a clump of grass, but it is also very noticeable in leeks, where the roots all emerge from the base of the swollen stem (for reference, bulbs are swollen stems transformed into storage organs, so they are not roots, which originate from below).

Some examples: leek, tulip, onion, grasses, maize, plantain…

Fasciculate root © Gwenaëlle David-Authier

Discover other Shrubs

View all →Available in 1 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

Available in 1 sizes

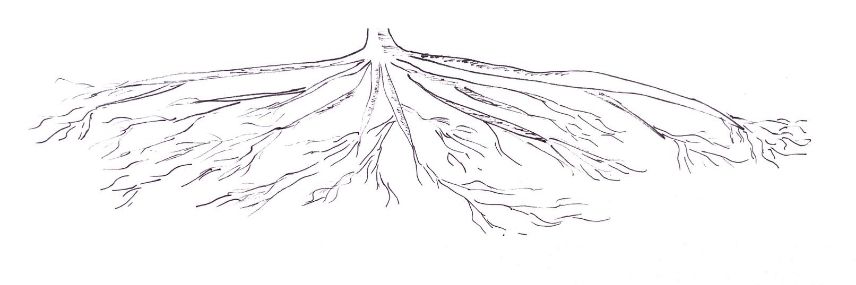

The running root system

In this case, the main root is underdeveloped, so it is the lateral roots that will take over. These will grow horizontally at shallow depth and regularly create a sort of mini-pivot root. This is where the effectiveness of certain groundcover plants in quickly colonising a given area comes from, but it is also true for some trees in our regions.

A few examples: poplar, willow, bamboo, beech, ash, and legumes (beans, peas, broad beans…).

Running root © Gwenaëlle David-Authier

Read also

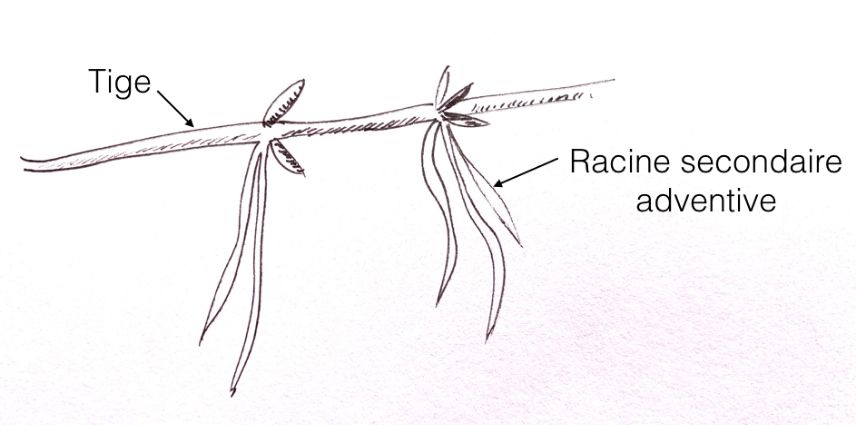

Trees and bushes: different habitsAdventitious roots

Often complementary to an initial root system, adventitious roots form on stems from a node. As soon as the stem touches the soil, roots appear, allowing a second shoot to grow. However, adventitious roots can also appear on the stem of certain plants (such as tomato or maize) above the “true” root system; this can be summarised as: “two root systems will be more effective than one!“

Some examples include: strawberry, mint, periwinkle…

Adventitious root © Gwenaëlle David-Authier

More anecdotal root systems

- climbing roots: as seen in ivy or climbing Hydrangea, these are adventitious roots that allow the plant to attach to a support (wall, tree…). They do not absorb nutrients and are therefore never harmful to the supporting tree;

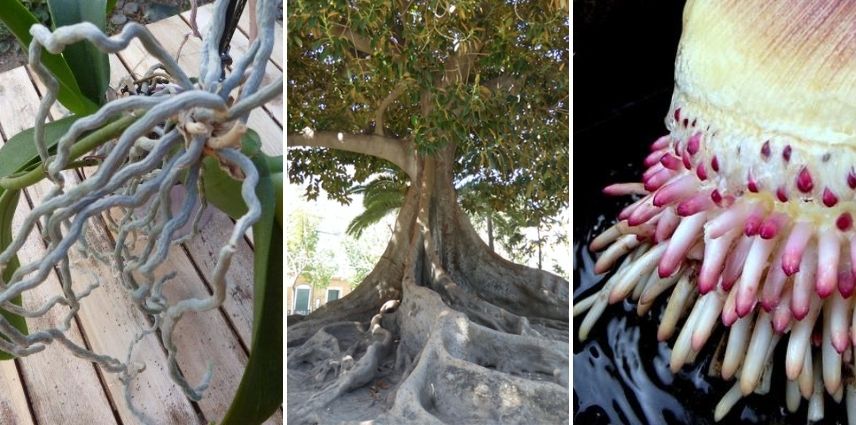

- aerial roots: they develop on the vegetative part of the plant and are designed to absorb atmospheric moisture. They are found in tropical plants, especially epiphytes (orchids, bromeliads, Tillandsia…);

- internal roots: surprisingly, inside a hollow but still living tree, roots can develop. They will draw nutrients from the humus formed in that area. The tree can then grow towards its centre and restore an internal bark;

- “storage” roots: like tuberised roots (tubercle) in buttercup or dahlia, or in some succulent roots that allow for water storage;

Tuberised root © Gwenaëlle David-Authier

Tuberised root © Gwenaëlle David-Authier

- structural roots: like stilt roots, these are adventitious roots anchored in the soil (mangrove trees) or buttress roots of the kapok tree that stabilise trees by rising along the trunk. These two types of roots help keep trees upright in very loose or shallow soils (equatorial forest);

- pneumatophores: these are vertical roots that emerge from the water and facilitate gas exchange, as seen in many mangrove or swamp trees (e.g., Bald Cypress);

- sucker roots: these are roots that allow the plant to “suck” water and nutrients directly from the supporting plant. This is the case for some parasitic or hemi-parasitic plant species like Mistletoe.

Aerial roots of an orchid (photo: Gwenaëlle David), roots of a kapok tree in the botanical garden of Cadiz (photo: Gwenaëlle David), bamboo roots (photo: Ken Ishikawa)

Aerial roots of an orchid (photo: Gwenaëlle David), roots of a kapok tree in the botanical garden of Cadiz (photo: Gwenaëlle David), bamboo roots (photo: Ken Ishikawa)

Did you know?

In reality, some plants, depending on the species as well as external interactions (human activity, soil, climate, humidity…), can adopt mixed root systems that may include: tap, fasciculate, or running roots simultaneously.

Roots interact with the soil’s flora and fauna. Thus, certain plants such as legumes and alder, for example, are capable of fixing atmospheric nitrogen from the air thanks to bacteria present in their roots.

Trees, but not only, live in symbiosis with fungi, allowing them to exchange nutrients and even “communicate” with each other: these interfaces are called mycorrhizae. Everyone benefits from this association: the fungus helps the plant absorb water and certain minerals from the soil, while the plant provides the fungus with carbon that it cannot synthesise due to lack of photosynthesis.

- Subscribe!

- Contents

Comments